Born in London on December 22, 1939 at the Paddington Hospital, Michael Andrew Bigg and his family survived bombings & evacuations during the World War II years and moved to the west coast of Canada when he was 8 years old. In his youth, he enjoyed exploring the British Columbia wilderness. According to his father, newspaper publisher Andy Bigg, Michael’s early life experiences ingrained in him with an immense love of nature. He attended Cowichan Senior Secondary School in Duncan, BC and then the University of British Columbia where he studied Falcons, Water Shrews and Harbor Seals. His Doctorate awarded in 1972, was based on the reproductive ecology of Harbor Seals.

Dr. Michael Bigg was a Canadian Oceanic Marine Biologist who is recognized as the founder of modern research on Killer Whales. With his colleagues, he developed new techniques for studying Killer Whales and conducted the first population census of the animals. Dr. Bigg’s work in wildlife photo-identification enabled the longitudinal study of individual Killer Whales, their travel patterns and their social relationships in the wild which began to revolutionized the study of cetaceans. In recent decades, the public has come to appreciate and be fascinated by Killer Whales.

However for at least a century before the mid-1960′s, Killer Whales were widely feared as dangerous, savage predators, a reputation based on rumor & speculation. In the waters of the Pacific Northwest, the shooting of Killer Whales was accepted and even encouraged by governments. The mid-1960′s and early 1970′s saw the development of public & scientific awareness of the species, starting with the first live-capture & display of a Killer Whale known as “Moby Doll“ that had been harpooned off Saturna Island in 1964. Between 1962 and 1973, an estimated 50 Killer Whales from the  British Columbia and Washington coasts were captured for display in captivity and at least 12 more whales died during capture attempts. It was assumed that the Killer Whale population in these waters numbered in the thousands, however as a standard wildlife-management practice for harvestable animals, the Canadian government determined that a census should be done. In 1970, Dr. Bigg became head of Marine Mammal Research at the Canadian Department of Fisheries & Oceans Pacific Biological Station in Nanaimo, BC and was given the task of this Killer Whale population census.

British Columbia and Washington coasts were captured for display in captivity and at least 12 more whales died during capture attempts. It was assumed that the Killer Whale population in these waters numbered in the thousands, however as a standard wildlife-management practice for harvestable animals, the Canadian government determined that a census should be done. In 1970, Dr. Bigg became head of Marine Mammal Research at the Canadian Department of Fisheries & Oceans Pacific Biological Station in Nanaimo, BC and was given the task of this Killer Whale population census.

Bigg’s first technique was to send 15,000 questionnaires to boaters, lighthouse keepers, fishermen and others in the general public who frequented the British Columbia coast, asking them to record Killer Whale sightings on one day. No other animal census of this kind had been performed anywhere in the world. The results of the survey taken on July 27, 1971 indicated that the number of Killer Whales in the British Columbia region of the area was at most 350, drastically fewer than had been assumed. Similar surveys in the following 2 years and subsequent work with photo-identification techniques substantiated the results.

In 1976, Bigg submitted his report indicating that the rate of captures from such a small population was unsustainable and recommending restrictions on the capture of Killer Whales from Canadian waters. The same year, the U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service conducted a Killer Whale survey in the Washington coast which also yielded low numbers and public opinion had begun to turn against whale capture. Since 1976, no Killer Whales in British Columbia or Washington waters have been taken for captivity with the exception of “Miracle”, a young whale that had been discovered starving and with bullet wounds. Killer Whales for aquaria continued to be taken from Iceland until 1989, when that country banned further captures. Since that time although Killer Whale populations at marine parks are in decline, only a few small-scale captures have occurred in Argentina, Japan and Russia.

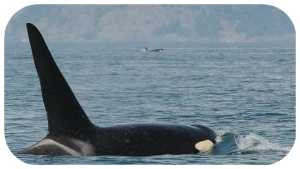

In the early 1970′s, Dr. Bigg and his colleagues discovered that individual Killer Whales can be identified from a good photograph of the animal’s dorsal fin & saddle patch, taken when it surfaces. Variations such as nicks, scratches & tears on the dorsal fin and the pattern of white or gray in the saddle patch, are sufficient to distinguish Killer Whales from each other. Although it had been recognized that the some animals could be identified from obvious distinctive features such as scars, Bigg and his colleagues discovered that the dorsal fin & saddle patch area of every Killer Whale was sufficiently distinctive to allow the individual to be reliably identified at sea using photographic techniques. The technique enabled the local population of Killer Whales to be counted each year rather than estimated. It also allowed latitudinal study of individual Killer Whales, their travel patterns and their social relationships in the wild and revolutionized the study of cetaceans. Just a few years previously, whale research had meant studying captive or dead animals and the study of living wild whales had been virtually nonexistent.

For Killer Whales, researchers arbitrarily chose the left side of the animal as the one to be used for identification. Dr. Bigg’s team of Killer Whale photographers & spotters  quickly grew to include hundreds of volunteers from along the coast, a project that was eventually formalized in 1999 as the British Columbia Cetacean Sightings Network. In 1975, researchers examining thousands of black-and-white photographs began to assemble a catalog containing a photograph of every Killer Whale in British Columbia’s waters, a catalog that has been continually updated and used to this day.

quickly grew to include hundreds of volunteers from along the coast, a project that was eventually formalized in 1999 as the British Columbia Cetacean Sightings Network. In 1975, researchers examining thousands of black-and-white photographs began to assemble a catalog containing a photograph of every Killer Whale in British Columbia’s waters, a catalog that has been continually updated and used to this day.

In 1976, federal funding for Bigg’s Killer Whale research ended and he was reassigned to other projects. It was not until the early 1990′s after Bigg had died, that the Department of Fisheries & Oceans again began to provide funding for whale research on the west coast. Still, Bigg continued his research on his own time for 14 years. Oceanic Marine Biologist Dr. Graeme Ellis who began working with Bigg in 1974 said that in the times that funding for Killer Whale research was absent, “It had become so fascinating, we couldn’t let it go. For many years, it was done with our own money and our own time.” In their book “Guardians of the Whales”, Bruce Obee and Dr. Ellis wrote: “Bigg and his colleagues discovered that resident killer whales travel in extremely stable matriarchal groups. While studying seals, sea lions or other species in the field, he disregarded departmental memos ordering him to forget about whales. He traveled the coast on his own time, soliciting help from anyone and everyone with his infectious fever. He’d think nothing of asking a float plane pilot to land beside a sport fisherman, then persuade the fisherman to run him over to a nearby pod of whales and click pictures for the rest of the day”.

During this time Dr. Bigg together with friends & associates, assembled what has been described as one of the most thorough data sets for any wild mammal, the Killer Whale was transformed from one of the least known to among the best understood of all cetaceans. His records included births, deaths, diet & social associations. Bigg and his colleagues gathered enough data to produce a complete family tree documenting the maternal-side relationships of every Killer Whale on the British Columbia and Washington coasts. One of the key discoveries of Bigg’s team was that there were 2 types of Killer Whales living near the British Columbia coastline, “residents” which ate almost exclusively fish and “transients” which hunted marine mammals and other warm-blooded prey. Resident & transient Killer Whale societies are separate and the 2 types tend to avoid each other. The resident Killer Whale population of British Columbia and Washington is further divided into 2 communities, one northern and one southern that do not interbreed.

Another discovery was that resident Killer Whales have one of the most stable social structures of any animal species. Pods of Killer Whales had previously been assumed to consist of a few adult males and a harem of potential female mates. Dr. Bigg’s team slowly realized that Killer Whale pods are matriarchal: Killer Whales travel not with their mates, but with their mothers and maternal relatives. The basis of resident Killer Whale groupings is the rule that each animal travels primarily with its mother throughout their lives. Although his research was based in the eastern North Pacific, Bigg mentored Killer Whale researchers from around the world who sought his advice for their own studies. Johnstone Strait is the summer home to a large number of Resident Killer Whales and includes the Robson Bight-Michael Bigg Ecological Reserve. Although he is best known for his work with Killer Whales, Bigg spent most of his career studying other marine mammals. He researched Northern Fur Seals in British Columbia and the Pribilof Islands of Alaska. In 1972, Bigg organized a transplantation of Sea Otters from Alaska to Vancouver Island, a population that continues to thrive. He also conducted research on Steller/Northern Sea Lions & Harbor Seals.

Pacific, Bigg mentored Killer Whale researchers from around the world who sought his advice for their own studies. Johnstone Strait is the summer home to a large number of Resident Killer Whales and includes the Robson Bight-Michael Bigg Ecological Reserve. Although he is best known for his work with Killer Whales, Bigg spent most of his career studying other marine mammals. He researched Northern Fur Seals in British Columbia and the Pribilof Islands of Alaska. In 1972, Bigg organized a transplantation of Sea Otters from Alaska to Vancouver Island, a population that continues to thrive. He also conducted research on Steller/Northern Sea Lions & Harbor Seals.

In 1984, Mike was diagnosed with leukemia. While ill, he continued to work to complete his final report on Killer Whales and was able to see it in print shortly before he died at the age of 51 on the evening of October 18, 1990. Mike is survived by his ex-wife Silke, a daughter Michelle, a son Colin who died in 2009, two sisters Carol & Pamela and his parents, Andy who passed away in 2003 & Irene who died in 1993. As his ashes were scattered in Johnstone Strait, a remembrance of the funeral was attendees and the press both noting that more than 30 Killer Whales appeared in the waters of Johnstone Strait in time for the ceremony. The Robson Bight Ecological Reserve in Johnstone Strait which was designated as a Killer Whale sanctuary in 1982, was renamed by the Canadian Government as the “Robson Bight-Michael Bigg Ecological Reserve”. The reserve includes one of the few “rubbing beaches” in the world where Killer Whales gather to rub against smooth underwater pebbles. A female resident Killer Whale born shortly before Dr. Bigg’s death in 1990, is unofficially named “M.B.” her official designation is G-46. Additionally, the Whale Museum in Friday Harbor, WA dedicated the name “Mike” to the resident Killer Whale J-26.

A funny story about Mike was told to me by his life-long friend Dr. Barry Jones: “Mike borrowed my brand new convertible in 1965 and used it to transport a live & quite large Harbor Seal in the back seat over to Vancouver Island by ferry from Vancouver. I never did get my car totally cleaned, but it wasn’t a big deal either. Mike is never forgotten in my life. He was my best friend, we were the same age, went to UBC together and traveled the world together. When I celebrate my birthday, I also celebrate his.”

A funny story about Mike was told to me by his life-long friend Dr. Barry Jones: “Mike borrowed my brand new convertible in 1965 and used it to transport a live & quite large Harbor Seal in the back seat over to Vancouver Island by ferry from Vancouver. I never did get my car totally cleaned, but it wasn’t a big deal either. Mike is never forgotten in my life. He was my best friend, we were the same age, went to UBC together and traveled the world together. When I celebrate my birthday, I also celebrate his.”

Mike’s ex-wife Silke reflected upon her years with him on Facebook: “He was my “Bigg” love and a wonderful father to Michelle & Colin. Would you believe we met around the procuring of the going price of seal skins ? True and unbeknownst to most, we  were a team in the early Killer Whale census project. As my new husband, he came with a dowry of 18 Gerbils would you believe and the honeymoon destinations? Well, those are comedic tales of the first order! Never mind all the other wildlife that joined our marriage from time to time and I’m not talking about the children! Stories that are just too unbelievably funny. You had to be there! Sense of humor required and scientists are not necessarily dull & boring folks. Some of you will remember and memories is what this is all about, right?”

were a team in the early Killer Whale census project. As my new husband, he came with a dowry of 18 Gerbils would you believe and the honeymoon destinations? Well, those are comedic tales of the first order! Never mind all the other wildlife that joined our marriage from time to time and I’m not talking about the children! Stories that are just too unbelievably funny. You had to be there! Sense of humor required and scientists are not necessarily dull & boring folks. Some of you will remember and memories is what this is all about, right?”

The “Dr. Michael A. Bigg Memorial Bursary” was created at the University of Victoria for students of marine biology in 2006. A year later, the Vancouver Aquarium created a scholarship program sponsored by the Wild Killer Whale Adoption Program. The “Michael A. Bigg Award” is presented annually to a graduate student whose thesis/dissertation research focuses on cetaceans toward the identification or conservation of cetacean habitat.