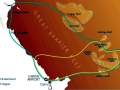

The below photos are from the Australian Bull Stingray attack & death of Steve Irwin on Monday September 4, 2006 in Australia’s Batt Reef, a coral reef off Port Douglas in Queensland, Australia. The reef region is centered at 16°24′S 145°46′E/16.400°S 145.767°E and is part of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef.

To the larger than life Australian whose death is capturing headlines all around the world, Steve “the Crocodile Hunter” Irwin made his reputation by pushing the boundaries and living on the edge of danger. Yesterday 30 kilometers (18.6 miles) off the coast of Port Douglas, he got just a little bit too close. News of Irwin’s death shocked his native Australia and fans around the world poured out their grief & condolences. The Australian Parliament interrupted its normal schedule so lawmakers could pay tribute to Steve Irwin, whose body was flown home to Beerwah today from Cairns. State Premier Peter Beattie said Irwin would be afforded a state funeral if his family agreed. “He was a genuine, one-off, remarkable Australian individual and I am distressed at his death”, Prime Minister John Howard said. John Stainton said that Steve was in his element in the Outback, but that he and Irwin had talked about the sea posing threats the star wasn’t used to. “If ever he was going to go, we always said it was going to be the ocean,” Stainton said. “On land he was agile, quick-thinking and quick-moving but the ocean puts another element there that you have no control over”. Immediately after the attack, Irwin was rushed to his nearby research vessel “Croc One”. A doctor aboard the ship was unable to resuscitate Irwin, who was dead by the time a rescue helicopter arrived. “He died doing what he loved best and left this world in a happy and peaceful state of mind”, Stainton said.

NEWS ANNOUNCEMENT of IRWIN’S DEATH

Steve Irwin’s last moments

Monday September 4, 2006 should have been a typical day’s filming for Steve “the Crocodile Hunter” Irwin but on that fatal morning, Irwin and his production team had their final discussion onboard Croc One about what they were going to film that day. As well as Irwin, the team he put together for this filming project included a pair of cameramen, Craig Lucas, a freelancer who had only recently completed an underwater course but had been picked by Irwin to help with the filming and Justin Lyons, who had filmed Irwin for many years. Also on his selected team were Philippe Cousteau, grandson of the famous ocean explorer Jacques-Yves Cousteau, Dr. Jamie Seymour, a marine biologist from James Cook University and John Stainton, Irwin’s long-time friend & manager who had “discovered” him and introduced him to the world. Croc One Skipper Chris Reed was also there. Justin Lyons gathered his camera equipment together as Irwin prepared himself for the dive. They climbed into the white inflatable dinghy and Irwin dove into the water. As an old mate, Lyons was accustomed to Irwin pushing the limits and getting into all kinds of scrapes. Once, they had visited the Indonesian island of Flores to film the huge Komodo Dragons. These reptiles grow to 3 meters and can effortlessly bite through an arm or leg. Irwin and the crew had a narrow escape, breaking a camera as they leaped out of harm’s way when one of the dragons charged. Lyons recalled later: “They’re sort of placid, but they can turn very quickly”. He was not to know how relevant those words would be when related to stingrays. About half a kilometer away, Pete West stood on the deck of his boat Deepstar with marine biologist & friend Teresa Carrette, while 2 of his dive crew were in the water checking equipment and getting ready for the afternoon’s filming. It was shortly after 11 am as they watched the white inflatable dinghy from Irwin’s launch bobbing about several hundred meters away. They guessed he was just below somewhere, probably no more than 2 meters down enjoying his swim with the stingrays. They hoped that Lyons and the second cameraman Craig Lucas who were down there with him, were getting some good footage.

As he continued going about his business on Deepstar, West paid no further attention to the dinghy until curiously, he heard its motor getting louder. The inflatable was racing towards Deepstar. West knew something was up. Then Lyons was yelling up at West: “It’s Steve! He’s been hit by a stingray!” West stared down in horror at Irwin lying face up and motionless on the floor of the dinghy beside Lyons’ camera. A chill ran through West. There was a wound in Irwin’s chest, right over the heart. Blood was spreading rapidly. West quickly glanced towards Croc One. There was no indication that anyone on board was aware of what had happened. A crew member put pressure on the wound while he tried to calm his friend. “I was saying to him things like think of your kids Steve, hang on, hang on, hang on” he said. “He calmly looked up at me and said, I’m dying” and that was the last thing he said… those were his final words.” West had some medical experience from his days working on oil rigs but he knew that the attention Irwin required was far beyond his expertise. In their almost blind panic, the men filled the air with expletives. They were a long way from the urgent kind of medical help that Irwin needed, but West believed he should be sped back to Croc One where the marine biologist Seymour might know what to do about such a terrible wound. As Lyons turned the dinghy around and raced at full throttle to the distant launch, West grabbed the radio handset and hit the emergency VHF channel 16. Frustratingly, there was no response from the Port Douglas Coast Guard on that channel, so he tried calling up help from the next nearest coast guard station in Cairns, some 50 kilometers south of Port Douglas. His voice was trembling as he made the call. It was 11:21 am. “Coast Guard Cairns! Coast Guard Cairns! This is Deepstar. We are in need of immediate medical assistance!” He received an immediate response. West did not say who the victim was in that first exchange but on Croc One skipper Reed heard the cry for help over his radio. Stainton and Reed dashed to the rear of the boat and saw the dinghy speeding towards them. They knew that something terrible had happened. Then they saw Irwin lying in his blood on the floor of the dinghy. The conservationist’s limp body was hauled on to the back duckboards after Stainton had cut free a second dinghy moored there and which was in the way. Seymour examined Irwin, but hope faded with every passing second. On the radio to Cairns Coast Guard, Seymour switched to the closed channel 73, so he could discuss further urgent action without interruption from other vessels’ skippers who would have picked up the initial distress call. Seymour commandeered the radio. He knew how bad it was. He told the Coast Guard that an emergency evacuation was needed.

The crew felt like they were living through a nightmare. Irwin, their friend, their workmate, was lying on the deck with what they feared was a fatal wound in his chest. He did not appear to be breathing. He was certainly not moving. They felt for a pulse and could find none. Yet there was not a man who was prepared to believe that Irwin was dead. Someone tried to administer the “kiss of life”. They tried kick-starting his heart with CPR to no avail. Stainton told himself that Irwin was dead yet he would not, could not, say it to anyone, although he suspected that the others were now thinking the same thing. There was one more desperate call to be made as, back on land an emergency helicopter was preparing to take off. Seymour called West on Deepstar and now West learned just how serious the incident was. “Do you have a defibrillator there?” asked Seymour. “Negative”, replied West. There were no heart-starters on his boat. “Oxygen yes but sorry, no defibrillator”. Now West knew from the question that Irwin’s heart had stopped. They were miles from anywhere. What hope did Irwin have now? Back on-board Croc One there was no question of just spinning around and racing at full throttle towards Low Isles, halfway between Batt Reef and Port Douglas, where there was a heliport. The slightest mistake and Croc One would hit the reef – the coral had to be negotiated with great caution. As Reed worked his way through the reef and then opened up the throttle, the crew crowded around the still body of Irwin, praying, cursing, hitting his chest, slapping his wrists. Terri was far away in Tasmania somewhere – what the hell were they going to tell her? As Croc One headed away into the distance, West turned his own vessel towards the abandoned inflatable that Irwin had been using. He recovered it and a second dinghy that had also been left behind. No one on Croc One cared about dinghies at a time like this. The underwater camera was still lying in the dinghy. West brought it into the main cabin. Lyons called up on the radio, concerned about the camera he had abandoned on the dinghy. Croc One had arrived at Low Isles at 11:50 am with the emergency helicopter team touching down only 10 minutes later.

West assured Lyons he had recovered the camera. “How’s Steve doing?” West then asked. There was a moment’s silence before Lyons replied: “He’s in the hands of professionals”. Then he continued: “The camera, can you make sure it’s secure and also ensure the tape isn’t stuffed. It’s vital”. West, familiar with the equipment, pressed the playback button. He and Carrette watched the last few seconds on the small viewfinder and were shocked at what they saw. There was a 2.5 meters (8.2 feet) stingray, with Irwin swimming above. They were about to watch a man die. West was to describe later how he saw graphic footage in a medium to wide shot as the large Australian Bull Stingray suddenly whipped up its deadly tail and struck Irwin in the chest with a barb. He knew then that Irwin had no chance of survival. In that fatal moment, Irwin instinctively grabbed the barb and tore it from his chest. It was the last move the “Crocodile Hunter” would make. The effort to keep him alive had been frantic. When Croc One reached Low Isles with the rescue helicopter still on the way, the crew of a charter boat Wave Dancer, owned by dive company Quicksilver also tried to revive him, this time with a defibrillator without success. Enid Traill a nurse who was on holiday, was taking a stroll around the island, mingling with some 50 other tourists enjoying a sightseeing or diving day out, when she heard someone counting “one… two… three!” Instinctively she knew what that meant. A medical emergency. Someone’s heart being pumped. Moments later, she saw a group of men carrying someone up the beach. It was a confusing scene, for there was a camera crew there too. She thought perhaps that it had just been a movie or a documentary after all, but the faces of the men were grim. It was too real. The holder of advanced resuscitation qualifications, she hurried over. “Can I help? I’m a nurse”. Heads nodded frantically. They carried the limp figure into a boat shed, Traill still unaware of who the man was. The daughter of the late Jack Spender known as “Mr. Lifesaving” in Queensland after setting up the association’s state headquarters, 55-year-old Traill took over the CPR. “I knew it was a terrible situation because we couldn’t get any air into his lungs,” she recalled later. “We tried and tried for 10 minutes or so, but it was all to no avail”.

The paramedics arrived on a Care Flight helicopter from Queensland Helicopter Rescue. The medical team also had no idea who the victim was. As they took over from Traill, she watched helplessly as they “examined the hole in his heart”. One of the paramedics asked: “Have we got an ID on this man?” Stainton stepped forward. “It’s Steve Irwin,” he said. There was a moment’s silence. “Are we talking about “the” Steve Irwin?” the paramedic asked. “Yes” said John. Traill looked to the medical team in shock. It was a terrible moment, one she would never forget for curiously, she had known Irwin as a teenager when he would call at her family’s marine refrigeration business in Caloundra to see one of the apprentices who worked there. “The fact that he was from home and someone I knew made the impact greater on me. I would rather say I wasn’t there, but I was.” She remembered how he would turn up at the workshop with lizards in his pockets and how in recent years, he would help to support fundraising activities for the Dicky Beach surf club that Traill is still associated with. Despite the efforts of everyone, on Croc One, on the shore of the island and in the boat shed, the conclusion was reached that Irwin was beyond all help. He was pronounced dead at 12:53 pm, some 90 minutes after he had received that fatal strike. “They told me he wouldn’t have survived even if he’d received that wound in an operating theater and there was medical help available on the spot,” Traill said. Care Flight Dr. Ed O’Loughlin confirmed the hopelessness. “It became clear fairly soon he had non-survivable injuries,” he said. Irwin’s body was flown to the mainland and then transported to the mortuary at Cairns Hospital. Could he have been saved if he had not torn the spike from his chest? It seemed unlikely, but in any case medical experts and marine specialists agreed that his instinctive reaction to rip it out before he lapsed into unconsciousness would have increased the damage. Having already been struck in the heart like a man being hit by a barbed arrow, jerking it out would have resulted in added tearing. Marine Envenomation Specialist Dr. Peter Fenner was convinced that the action would have made matters much worse, “the more you start pulling things around, the more damage you do to yourself,” he said as the shock news spread around the world. A scientist at the Australian Venom Research Unit at Melbourne University Dr. Bryan Fry, believed that leaving the barb in the chest would have stemmed the bleeding, whereas pulling it out would have taken a lot of force and would possibly have caused more damage. The serrations he said, meant the spike would not slide out like a knife. Generally said a surgeon Dr. Hugh Wolfenden, who works at the Prince of Wales Hospital in Sydney, it would not be advisable to remove an object because while still in place it helps to stem the bleeding. On the other hand, leaving it in the heart could also be problematical if the heart was still beating because the action of the heart could result in it lacerating itself against the foreign object. As for the poison, experts were divided on whether it would have killed Irwin. Geoff Isbister, a clinical toxicologist based at Newcastle’s Mater Hospital north of Sydney, believed that although the venom might have caused tissue damage, the physical trauma to Irwin would have been enough to end his life.

WITNESS TO STEVE IRWIN’S DEATH

The World Today – Tuesday September 5, 2006 – 12:10:00 pm

Reporter: Lisa Millar (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)

LISA MILLAR: Looking pale and upset, Steve Irwin’s long-time friend and business manager John Stainton joined the police media conference this morning in Cairns. He’d been on the boat with Mr. Irwin yesterday and they’d shared an early morning cup of tea, his friend telling him he’d never been happier. Now Mr. Stainton has had to watch the confronting footage of his friend’s death.

JOHN STAINTON: I did see the footage and it’s shocking. It’s a very hard thing to watch, because you are actually witnessing somebody die and it’s terrible.

LISA MILLAR: What does it show, John?

JOHN STAINTON: It shows that Steve came over the top of the Australian Bull Stingray and then the tail came up and spiked him here and he pulled it out and the next minute he’s gone. And that was it and then the cameraman had to shut down.

LISA MILLAR: How close would he have been to the ray at the time?

JOHN STAINTON: Umm, probably, a meter maybe? Coming over the top of it.

LISA MILLAR: Steve Irwin always thought too close was never close enough when it came to the dangerous creatures he filmed for audiences around the globe.

JOHN STAINTON: There’s been a million occasions that we, probably both of us, held our breath and thought, gee, we are lucky to get out of that one. And I mean, I’ve had to look at vision back sometimes with snakes, because they’ve been so close to him, but he just seemed to have a charmed life, that nothing he did…

LISA MILLAR: But Police Superintendent Mike Keating says there is nothing suspicious about what happened on Bat Reef just before noon on Monday.

MIKE KEATING: At the time of his death Mr. Irwin was interacting with an Australian Bull Stingray on the Great Barrier Reef, there is no evidence that Mr. Irwin was intimidating or threatening the stingray. My advice is that he was observing the stingray. There are no suspicious circumstances in relation to the death of Mr. Irwin. And as with all deaths, the police will interview witnesses and report on the death to the coroner.

LISA MILLAR: The video tape is now part of the investigation. Once the coroner has finished his report, Mr. Irwin’s body will be released. Mr. Stainton will take Steve’s body back to the Sunshine Coast where Mr. Irwin’s wife Terri and children Bob and Bindi have been flown in from Tasmania.

JOHN STAINTON: I think she’s been very strong and I think for their children’s sake, she has to be strong because they’re very impressionable ages, you know. Bindi is eight and little Robert’s coming up to three. So he may not understand totally, but Bindi certainly does. And she’s very mindful of how she has to control her emotions to get the kids though it.

LISA MILLAR: Mr. Stainton says the man who was known around the world as the Crocodile Hunter ploughed everything he had into wildlife conservation and had just spent the best month of his life researching saltwater crocodiles on Cape York. But it was ironically not on land, but in the sea that the Crocodile Hunter came undone.

JOHN STAINTON: It was… the actual thing that he was shooting was for Bindi’s new TV show, which was about to start next week when we go back and it’s the thing that he was doing at that point. I mean, considering that the program that we were shooting, the documentary, was called Ocean’s Deadliest, it was just ironic. It was ironic, because when you start out on those sort of programs, you always think, gosh, we’re going to be dealing with everything that could kill you and knowing Steve wants to touch everything, we are really in a dangerous situation. I was always aware of that we were probably heading into a darker territory with this show. But he was always in control and he was always, he was just invincible.

LISA MILLAR: He will always remember though, the last moments they spent together.

JOHN STAINTON: And he gets up at, probably three o’clock every morning, he is not a very good sleeper (cries). We sat together in the early hours in the morning having a cup of tea, just talking about how good life was and how good the documentary was going to be and how, if he had the opportunity to shoot some bits for Bindi’s new TV show that day, now the sun was coming out and he was just in such a good frame of mind. You know it was like, there was nothing, no problems, no nothing to worry about. He was as happy as I’ve ever seen him. And that was the sad thing about it.

LISA MILLAR: And he treasures what Steve Irwin was able to achieve in his short life.

JOHN STAINTON: And he always said to me, if I can touch an animal, I’ll make people touch their hearts. And that was his philosophy, it was his belief, that by interacting with animals he was actually giving people something to love there, that they could feel that the snake or the crocodile was a human… you know, a personality and an individual, that he… that they weren’t ugly monsters. And he did. The evidence we had over the years that, you know, people turning their beliefs around from wanting to kill snakes and saying that the only good snake’s a dead snakes, to kill crocodiles, cull crocodiles, trophy hunt crocodiles, he played a very important role in changing people’s thinking in the world. And the amount of emails that we’ve had, millions of emails over the years from people in America that would say, we used to run over a snake on the road, but now we swerve around it. Those little things, you can’t say how many there were, there was millions.

Interview with Cameraman Justin Lyons

The only person to witness the moment Steve Irwin was pierced in the chest by a Australian Bull Stingray barb said the injuries were so severe that the Australian TV naturalist could not possibly have been saved. Justin Lyons, a regular underwater cameraman for Irwin and a close friend, said the jagged barb punctured Irwin’s chest dozens of times, causing a massive injury to his heart. “He obviously didn’t know it had punctured his heart but he knew it had punctured his lung,” Lyons told Australia’s Network Ten television. “He was having trouble breathing. Even if we’d been able to get him into an emergency ward at that moment, we probably wouldn’t have been able to save him because the damage to his heart was massive. As we’re motoring back, I’m screaming at one of the other crew in the boat to put their hand over the wound and we’re saying to him things like, ‘Think of your kids Steve, hang on, hang on, hang on.’ He just sort of calmly looked up at me and said, ‘I’m dying’ and that was the last thing he said.” Irwin and Lyons were just over a week into filming a series called “Ocean’s Deadliest” on the Great Barrier Reef in September 2006 when they took an inflatable boat a short distance from the main vessel carrying the rest of the crew in the hope of finding a Tiger Shark, Lyons said. Instead they came across a 2.4 meters (7.87 feet) Australian Bull Stingray and entered chest-deep water to film it. Stingrays are usually calm and will just swim away if frightened, he said. The final shot was to be of Irwin swimming up to the Australian Bull Stingray, with Lyons then filming it swim away. “I had the camera on. I thought – this is going to be a great shot, fantastic. All of a sudden it propped on its front and started stabbing wildly with its tail, hundreds of strikes in a few seconds,” said Lyons.

He assumes the animal mistook Irwin’s shadow for a Tiger Shark. Lyons said he initially did not realize his friend was hurt: “I panned with the camera as the stingray swam away. I didn’t even know it had caused any damage. It wasn’t until I panned the camera back and Steve was standing in a huge pool of blood that I realized something had gone wrong.” While Irwin was in “extraordinary pain” from the venom on the barb, Lyons said, the naturalist believed he had only punctured a lung. It was only when Lyons helped put Irwin on the inflatable boat he realized the extent of the damage. “It’s a jagged, sharp barb and it went through his chest like a hot knife through butter.” Lyons added: “He had a two-inch wide injury over his heart, with blood and fluid coming out of it.” Irwin was returned to the main boat and Lyons tried to revive him: “We hoped for a miracle. I did CPR on him for over an hour before the medics came, but pronounced him dead within 10 seconds of looking at him.” Another cameraman filmed attempts to save him, following Irwin’s strict orders that anything that happened to him during filming should be recorded. Lyons said he did not know what had happened to the footage and did not think it should ever be shown in any form: “Never. Out of respect for his family, I would say never.”