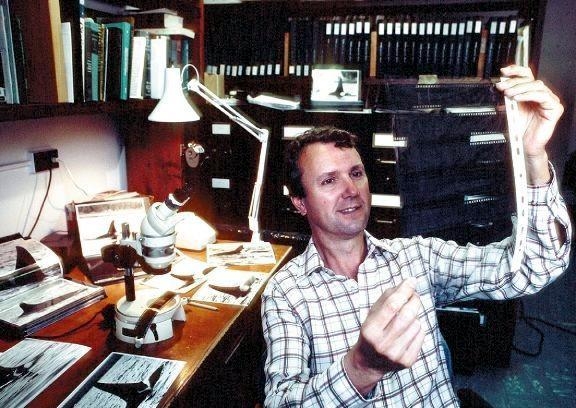

Believed to have been taken in 1985, Oceanic Marine Biologist Dr. Michael A. Bigg is shown in his office at the Pacific Biological Station in Nanaimo, BC. Scientists worldwide want to re-name mammal-eating Transient Killer Whales as “Bigg’s Killer Whales” to honor Bigg who died in 1990. He is considered to be without question, the “Founding Father” of the modern scientific studies of Killer Whales.

Believed to have been taken in 1985, Oceanic Marine Biologist Dr. Michael A. Bigg is shown in his office at the Pacific Biological Station in Nanaimo, BC. Scientists worldwide want to re-name mammal-eating Transient Killer Whales as “Bigg’s Killer Whales” to honor Bigg who died in 1990. He is considered to be without question, the “Founding Father” of the modern scientific studies of Killer Whales.

They roam as far north as the Arctic Ocean and are known as “transients” to distinguish them from fish-eating “resident” Killer Whales. If oceanic marine biologist Dr. John K.B. Ford has his way, school children one day will study a kind of North Pacific Killer Whale that preys on warm-blooded creatures such as Sea Otters, Harbor Seals and Sea Lions as well as Gray Whales, Humpback Whales and seabirds. Ford and colleagues worldwide, want Transient Killer Whales to be declared their own species and they want them to have a new name “Bigg’s Killer Whales” in honor of Dr. Michael A. Bigg.

(Bigg’s Killer Whales)

Bigg was the lead-researcher whose observations off British Columbia & Washington state led to the identification of transients and whose mentoring inspired a generation of researchers still uncovering the mysteries of the animal at the top of the marine food chain. “He was really very much the founding father of modern scientific studies regarding Killer Whales”, Ford said from his office at the Pacific Biological Station in Nanaimo, BC where he heads West Coast cetacean research for Canada’s Department of Fisheries & Oceans.

Dr. Paul Wade, a U.S. Killer Whale expert at the National Marine Mammal Laboratory in Seattle, said colleagues have begun using Bigg’s Killer Whales as the common name for transients in research papers. “It seems to be catching on”, Wade said. Work demonstrating that Bigg’s Killer Whales are a separate species also is progressing he said and that could lead to honoring Dr. Bigg with a formal scientific name for transients.

Michael Andrew Bigg was born in London in 1939. He moved to British Columbia with his family nine years later. He had a lifelong fascination with predators, Ford said and for a time was a Falconer. “He was kind of a rare generalist as a biologist”, Ford said. “He was broadly interested in natural history”. Just out of graduate school in 1970, Bigg was hired as a marine mammal biologist at the Pacific Biological Station. One assignment was an investigation of the status of Killer Whales, considered at the time extremely dangerous to humans and pests by salmon fishermen. By 1973, aquariums were paying $70,000 for a live Killer Whale and 48+ had been captured for display. Bigg & colleagues distributed sighting forms to fishermen and other coast residents. His report in 1976 concluded that just 200 to 350 Killer Whales remained along the British Columbia & Washington coasts, far fewer than thought and too few to sustain additional live captures.

He also made a breakthrough that would create the framework for decades of additional research. He determined that individual whales could be identified by pigmentation patterns on the saddle patch at the base of their dorsal fins. That meant researchers could track whales to figure out their diets, family dynamics and communications with other whales. “It was Mike’s realization that with a good-enough photograph, you could identify even the plainest looking fin without any obvious markings”, Ford said. Bigg’s formal association with Killer Whales ended by early 1977. He was reassigned to other marine mammals, including Northern Fur Seals Ford said, but kept at Killer Whale research on the side. He had started to distinguish families of resident Killer Whales that he suspected were targeting Salmon. More rarely seen were Killer Whales that Mike at first suspected were pod outcasts.

They turned out instead to be mammal-eaters. Genetic work on transients followed. Dr. Wade collaborated with National Marine Fisheries Service research molecular geneticist Phillip Morin and 14 other researchers on a 2011 paper that indicated resident and transient Killer Whales don’t eat or behave the same ways. They also don’t interbreed.“The evidence suggests that the transients in particular are quite different from everybody else and probably shared an ancestor about 700,000 years ago”, Morin said from the Southwest Fisheries Science Center in La Jolla, CA.

The scientists say at least 3 Killer Whale species likely roam the North Pacific including offshore Killer Whales and 3 in the Antarctic. Killer Whales are found in every ocean and DNA samples have been studied from the extreme north & south parts of the globe. Researchers are preparing to analyze samples from tropical & temperate waters Morin said, to piece together the pattern of evolutionary divergence between types. “The goal is to then try to compile the genetic data with all of other data — the behavioral, the acoustic, other molecular data, distribution — and come up with a description of Killer Whales globally, along with our recommendations for which should be species and which should be subspecies, if the data hold up those categories”, Morin said.

“Dr. Bigg’s influence on other scientists may have been as meaningful as his research. He shared his work and often his home with newly graduated marine biologists from the United States, France, Sweden, Norway, Mexico and Argentina, inviting them to unlock additional secrets about Killer Whales in their parts of the world”, Ford said.

Mike was diagnosed with leukemia in 1984 and died in 1990 at the age of 51. The idea for naming transients Ford said, came from the Vancouver Aquarium researcher Dr. Lance Barrett-Lennard & Dr. John Durban of the Southwest Fisheries Science Center.