Personal Acknowledgments

Upon my retirement in June of 2008, the digital conversion of this paper was completed after the many years since its acceptance & publication and is hereby dedicated to the following individuals. Each gave of their extraordinary assistance to my career within the marine biological sciences combined with the success of my K-12 outreach science program “OCEAN TREASURES”during its 19-year presentation span to educational communities worldwide and will always be forever truly appreciated:

Dr. Michael A. Bigg

Stan L. Waterman

Dr. Erich J. Hoyt

Dr. Lanny H. Cornell

Dr. John K. Ford

Dr. Richard M. Sears

William W. Rossiter

Dr. Robbins W. Barstow

Dr. Miguel A. Iñiguez

Dr. Arthur B. Mansfield

Dr. Robin W. Baird

Dr. Graeme M. Ellis

Dr. Ian B. MacAskie

Dr. J. Stephen Leatherwood

Dr. Paul J. Spong

Kenneth C. Balcomb III

Thomas A. Lincoln

Dr. David E. Sergeant

José Truda Palazzo, Jr.

Dr. John D. Hall

Dr. Johann W. Sigurjonsson

Dr. John N. Lien

Dr. R.S. Lal Mohan

Donald A. Sineti

Dr. Ivan D. Christensen

Dr. Edward M. Asper

Jacques-Yves Cousteau

Peter S. Benchley

Dr. Robert S. Kurson

Dr. Samuel H. Gruber

Dr. Peter C. Beamish

Dr. Murray S. Newman

Dr. Marilyn E. Dehlheim

Dr. Linda R. Wilson

Dr. Christian T. Lockyer

Kenneth S. Norris

Dr. Pamela J. Stacey

Dr. Ingrid N. Visser

Dr. Berne J. Würsig

Dr. Robert L. Brownell

Rodney E. Fox

Dr. James D. Darling

Dr. Christoph C. Guinet

Dr. Charles A. Mayo

Dr. James E. Heyning

Dr. Richard R. Reeves

Dr. Jon E. Krakauer

Dr. William E. Schevill

Dr. Susan H. Shane

Dr. William R. Watkins

Oceanic Marine Mammal Research

University of British Columbia

Vancouver, BC

Canada

FIELD RESEARCH, CASE STUDIES and

GEOGRAPHIC VARIATIONS of the

KILLER WHALE “Orcinus orca”

Gregory R. Mann

Doctoral Candidate

ABSTRACT

The Killer Whale (Orcinus orca) is well known worldwide, as a predator of other oceanic marine species including the larger rorqual whales. Not all known behavioral interactions however between Killer Whales and other oceanic marine species results in direct predation. Other forms of documented species interactions include harassment by Killer Whales, multiple species feeding within the same area, smaller cetaceans playing around the known predator who apparently ignores a possible food source and even apparently unprovoked attacks upon Killer Whales by larger pennipeds. These other types of interactions are more common than most people believe. The goal of this paper is to present such scientific information which will conclude that Killer Whale vs Marine Mammal interactions are extremely complex, involving many different factors which conducted field research by the scientific community is just beginning to understand.

At the outset, I wish to acknowledge and sincerely thank the prestigious members of the Doctoral Review Board of the University of British Columbia, for the opportunity to present this paper as a candidate for my Ph.D. in Oceanic Marine Biology.

INTRODUCTION

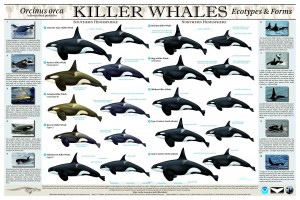

Only a singular species of Killer Whale is recognized in the world. However, there appears to be many localized races that differ in appearance, behavior and other lesser-known biological traits. Soviet biologists in September 1989, proposed a second species (Orcinus glacialis) from the Antarctic region, which they have characterized as having a smaller size and a variety of differences in diet, reproduction, appearance and behavioral traits.

The submitted new species has not yet been fully accepted by the world’s scientific community and this species is considered as a distinctive race of the same known species of Killer Whale. What is believed in the world’s scientific community is that there are indeed 2 separate races of the species. Known as “residents” & “transients”, both species live off the coastline of the Pacific Northwest region and are known to differ in appearance as well as many other biological aspects.

Possibly the most defiled of all animals on planet Earth, the Killer Whale has been branded by mankind as a ferocious & indiscriminate killer of oceanic marine wildlife and occasionally, even humans. The scientific name given to his oceanic marine mammal, even translates into a fearful and descriptive message. From earliest times, the Latin connotation means simply “the bringer of death”.

Moreover, the word “Orca” as used in the nomenclature of the general public simply denotes in Latin as “Whale” and thus, is inappropriate for further use in this paper. The word itself was created by the Sea World facilities several years ago, as a marketing tool used in their overall display especially marketing towards the newborn Killer Whales at their various venues. Instead of marketing the newborns as the little “Baby Killers”, they could simply advertise them as the little “Baby Orcas” which in the world of marketing would ease the harshness of the word from a general public point of view. If this were not the case, then False Killer Whales (Pseudorca crassidens) and Pygmy Killer Whales (Feresa attenuata) would be called False Orcas & Pygmy Orcas which they are not.

In recent history, large numbers of these powerful marine mammals were slaughtered by humans simply because these cetaceans lived within the same geographical areas where fishermen set their nets. Scientific studies conducted within the field and a 21-year history of Killer Whales held captive in various worldwide oceanographic facilities, now paints a completely different picture of this oceanic marine predator. Many scientists now recognize Killer Whales, as an important member of the oceanic food chain and a vital link of the overall ecology of the world’s ocean habitat in which they dwell.

Killer Whales have shown very little fear of humans and current research has shown of confirmed reports of Killer Whales having killed a human in the wild. Marine Biologists who have worked & studied these small cetaceans at marine wildlife parks, have recognized this species of having an extremely high level of intelligence and cooperative behavior. It remains very difficult however, to discuss this marine animal without using some type of superlatives.

Writers for centuries have described the Killer Whale as the fastest, strongest, deadliest and highest form of intelligence within the world’s oceans. There is strong evidence to support the use of varied descriptive terms but on the other hand, the widespread opinion that any swimmer or diver encountering a Killer Whale in the open ocean is doomed to the fate of Jonah, seems to be entirely without supporting evidence.

Undoubtedly the smaller family of cetaceans which includes the Killer Whale, is the most intelligent group of animals among all oceanic marine species. Researchers worldwide, have never truly had the quality opportunities to test this specie’s learning capacities, even under captive conditions but other small cetaceans have been tested extensively and are thought to possess a higher degree of intelligence than dogs. It should be emphasized however, that no reliable evidence substantiates the sensational claim of a few researchers and writers, that porpoises & dolphins may be as smart as humans. It does seem to be true however, that Killer Whales share at least one dubious distinction with humans, the so-called “killer instinct”.

Among all the world’s land & marine mammals, these are the only species that are known to kill other animals for the sheer sport of killing. Whether or not such behavioral traits denote a higher degree of intelligence remains an unsettled and unsettling proposition.

The Killer Whale is the largest member of the small-toothed cetaceans known in scientific terminology as Ocean Dolphins (Delphinidaes). Often called “Grampus”, “Blackfish”, “Broadfin”, “Fatchopper” or “Whalekiller”, these oceanic marine mammals are sometimes confused when sighted in the open ocean with the False Killer Whale (Psuedorca crassidens) or the Long-Finned Pilot Whale (Globicephala melanena). In pure fact, there is little reason to mistakenly identify any other cetacean species for a Killer Whale.

It’s large but streamline form and striking black & white patterns combined with its known swimming and feeding behaviors, is quite unlike any other form of oceanic marine wildlife. Dark black over most of its dorsal & lateral surfaces, the Killer Whale has a small oval-shaped white patch directly above and behind each of its eye regions. The ventral surface feature of the body is brilliantly white in color.

In the abdominal region, dorsal-lateral to the dorsal fin, a pale gray patch classified as the “saddle” is located which researchers have found to be an individual whale’s identifying mark or id tag, much like a human finger-print. Dr. Michael A. Bigg is given full credit to the discovery of this break through documentation which has led to other members of the cetacean family similarly being recorded in a like manner. Due to this uniquely difference among Killer Whales, each animal can be classified & cataloged during population census or pod identification photographing.

Adult males or bulls in particular, can hardly be mistaken for any other type of animal, which lives in the world’s oceans when sighting its narrow, pointed dorsal fin that may extend to 7’ above the back.

Repelling a popular belief, the dorsal fin contains no type of bone or skeletal structure and is instead, made entirely of cartilage much in the same structure as the human nose region. The dorsal fin is sometimes seen bent over or wavy especially in older males, due to the increased weight by growth during an individual’s lengthy life span and has nothing to do with whether the individual is captive or not.

Females or cows have a much smaller curved dorsal fin, which is very similar to the dorsal fins of several other small cetacean species for which mistaken identifications often occur. The females however, possess the same basic coloration markings, which match directly with the males.

Killer Whales are very well equipped for their unique lifestyle, with 34 conically-type teeth within their massive jaw. Capable of grasping & swallowing the entire body of a porpoise, seal or dolphin, this fact about Killer Whales made for an individual case that was reported and even now, is often misquoted & embellished. Dr. Everhard J. Slijper of the Icelandic Research Institute wrote in his classic book “Whales & Dolphins” of 32 Pacific Harbor Seals (Phoca vitculina) combined with other various dolphin species being removed from the stomach of a 24’ male taken in the Bering Sea off the southern coastline of Alaska.

In a much earlier documentation published in which my research has shown to have truly grown with rumors over the years, Dr. Daniel F. Eschricht reported a scientific result from a March 1861 field expedition. Dr. Eschricht’s field journals recorded the discovery during a dissection of pieces of 13 Ribbon Seals (Phoca hispida) as well as other various porpoises & dolphin species among the stomach contents of a 29’ bull taken off the eastern coastline of Iceland. These accounts are often misquoted and have been in recent past history, a prime source of the Killer Whale’s bad reputation.

In all know physical characteristics, the Killer Whale appears to be very successful from both a scientific & evolutionary point of view as well as one of the most advanced of all marine or land animals. Furthermore, they seem to have no natural predators other than humans. Even the whaling industry seldom bothers to harvest these small cetaceans, due largely to their rather limited body oil content. At present however, Japan and the Soviet Union are still conducting the largest fishery of Killer Whales for harvest. Located near the continent of Antarctica, the Russian & Japanese whaling fleets take up to 600 animals per year. Along the coastal regions of Iceland and Greenland, countless conflicts between Killer Whales and local fishermen have resulted in the periodic slaughter of hundreds of these marine mammals. In the past decade however, the Icelandic government has approved the creation of a live-capture fishery of Killer Whales to transplant them into remote northern waters.

Some of these captured animals are also shipped to the United States as well as other countries, for display and scientific research in many marine-life oceanography facilities. To discuss this research a step further, the International Whaling Commission (I.W.C.) as a direct result of an immediate moratorium passed during their 1980 Annual World Conference, completely banded all commercial whaling of smaller cetaceans including the Killer Whale.

The fact that Killer Whales are not more common however, is not a direct result of recent whaling methods. Ongoing research has discovered that their slight numbers may be due to the limited effect upon their available food supply or quite possibly, be a direct effect of a higher than normal birth mortality rate.

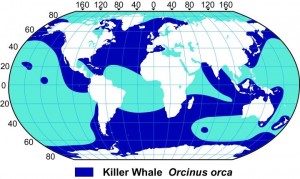

This is probably the most cosmopolitan of all cetaceans and can be seen in literally any marine region. Sightings of “Orcinus orca” occur throughout all oceans and contiguous seas, from equatorial regions to the polar pack-ice zones. However, it is most numerous in coastal waters and cooler regions where productivity is high.

In the Atlantic it ranges north to Hudson Strait, Lancaster Sound, Baffin Bay, Iceland, Svalbard, Zemlya Frantsa Iosifa and Novaya Zemlya; its range includes the Mediterranean Sea. In the Pacific it ranges north to Ostrov Vrangelya, the Chukchi Sea, and the Beaufort Sea. In the Southern Ocean, the range extends south to the shores of Australia and the Philippines, South Africa, South America and Antarctica, including the Ross Sea at 78°S.

Data from the central Pacific are scarce. They have been reported off Hawaii, but do not appear to be abundant in these waters.

Distribution of Orcinus orca: this species is found in all regions of the world, particularly in the Polar Regions

In the north-eastern Pacific, photo-identification studies yielded at least 850 individuals in Alaska, 117 off the Queen Charlotte Islands, 260 “resident” whales and 75 “transient” whales off eastern and southern Vancouver Island, 184 off the coasts of California and 65 off the Mexican west coast. Note that photo-identification techniques result in a minimum count of animals. In a more recent estimate, comes to a total population count of 1,500 Killer Whales in the northeastern Pacific. In the North Atlantic, questionnaire surveys yielded 483 to 1,507 Killer Whales for Norwegian coastal waters. Sightings in the eastern North Atlantic gave rough estimates of around 3,100 Killer Whales for the area comprising the Norwegian and Barents Seas, as well as Norwegian coastal waters and some 6,600 whales for Icelandic and Faeroese waters. Off the Japanese coast the estimate is 1200 individuals north of 35°N and 700 south of 35°N. For Antarctica, the most recent estimate is 80,400 Killer Whales south of the Antarctic convergence and for the Southern Indian Ocean, issued reports show a strong decline in the coastal waters of Possession Island between 1988 and 2000.

Sightings range from the surf zone to the open sea, though usually within 800 km of the shoreline. Large concentrations are sometimes found over the continental shelf. Generally, Killer Whales prefer deep water but they can also be found in shallow bays, inland seas and estuaries but rarely in rivers.

They readily enter areas of floe ice in search of prey. Resident Killer Whales in Pacific Northwest waters use regions of high relief topography along salmon migration routes, whereas transient Killer Whales forage for pennipeds in shallow protected waters.

In the Pacific Northwest, calving occurs in non-summer months, from October to March. Similarly in the Northeast Atlantic, it occurs from late autumn to mid-winter. Pods of resident Killer Whales in British Columbia and Washington represent one of the most stable societies known among non-human mammals; individuals stay in their natal pod throughout life. Differences in dialects among sympathetic groups appear to help maintain pod discreteness. Most pods contain 4-55 whales with resident pods tend to be larger than those of transients. Social organization can be classified into communities, pods, sub pods, and matriarchal groups: a community is composed of individuals that share a common range and are associated with one another; a pod is a group of individuals within a community that travel together the majority of time; a sub pod is a group of individuals that temporarily fragments from its pod to travel separately; and a matriarchal group consists of individuals within a sub-pod that travel in very close proximity. Matriarchal groups are the basic unit of social organization and consist of whales from 2-3 generations. Membership at each group level is typically stable for resident whales, except for births and deaths.

Being a apex predator, the Killer Whale utilizes the available resources in a complex fashion. Killer Whales often associate with other marine mammals (cetaceans and pennipeds) without attacking summarize that the typical size of a transient Killer Whale pod is consistent with the maximization of energy intake hypothesis. Larger pods may form for the occasional hunting of prey other than Harbor Seals, for which the optimal foraging pod size is probably larger than 3 and the protection of calves and other social functions.

Killer Whales are best known for their habits of preying on warm-blooded animals: they have been observed attacking marine mammals of all groups, from Sea Otters to Blue Whales. However, they often eat various species of fish & cephalopods and occasionally seabirds & marine turtles. Pods often co-operate during a hunt. Relationship with the prey is complex: pods tend to specialize and may frequently ignore potential prey as well as observations of Killer Whales feeding on Atlantic Herring (Clupea harengus) in a fjord in northern Norway using underwater video. The whales co-cooperatively herded Herring into tight schools close to the surface.

During herding & feeding, Killer Whales swam around and under a school of Herring, periodically lunging at it and stunning the Herring by slapping them with the underside of their flukes while completely submerged. While Herring constitute the whales’ main diet in Norwegian waters, Cod, Flatfish and cephalopods are the primary components off Japan.

In Puget Sound, the main food of resident Killer Whales during the summer and fall is Salmon. Most food items are swallowed whole. However, when whales attack larger prey, they rip away smaller pieces of flesh and then consume them. The tongues, lips, and genital regions of baleen whales seem to be the favored parts. Killer Whales consume fish of commercial importance. Troll catches of salmon show a decline when Killer Whales are in the area and damage to fishing gear has also been reported. Off Iceland, Killer Whales are attracted to Herring operations. Long line fisheries interactions involving Killer Whales have also been observed. Killer Whales are known to follow fish-processing vessels for many miles feeding off discarded fish. In the Bering Sea, the same pod of whales was reported to follow a vessel for 31 days for approximately 1600 km.

FIELD RESEARCH DEVELOPMENTS

Extensively conducted field research and subsequent data has shown that a dominant female leads a typical Killer Whale pod or family. All offspring including the males remain with their mother throughout a normal life span. When the matriarch female dies or becomes to old to reproduce, the next oldest female usually the oldest daughter assumes the role as pod leader.

A cow generally produces 1 calf every 2 years, with a standard gestation period lasting from 13-16 months in length. The female’s mammary glands are located on the underside of the body near the tail. Strong muscles allow her to squirt large quantities of extremely rich milk into a calf’s mouth as it dives beneath her. Newborn calves are on the average, about 6’ in length and an estimated 400 lbs at birth. Immediately after a birth, the attending females of the pod act as Nannies to form a type of living-nursery as well aid to protect the infant from predatory sharks and occasionally even the males of the pod and assist with the overall care of the newborn.

Bulls attain a known average length of 26’ but there have been recorded sightings of lengths obtaining over 30’+. The average normal weight of a male is an estimated 7-8 tons but individuals have been recorded from cropping captures of 9-10 tons in weight. Each side frontal flipper known as a “pectoral fin” is extremely broad & rounded, like a ping-pong paddle.

Each fin on an average adult bull, may reach a length of 7’ with an average width of as much as 4’ across. The overall width of the tail flukes from tip to tip on an average male, may extend an approximated 9’ across. The coloration, although previously mentioned, vastly changes in the young. The described white pattern areas are often pale-yellow to light brown during an infant’s first years.

Although extremely rare, all-white individuals have been sighted and even captured. In April 1970, field specialists of Washington’s “Sealand of the Pacific” captured such an animal and held it in their holding facility at Peddler Bay on the British Columbia mainland. The captured “albino” Killer Whale was nicknamed “Chimo” and was kept alive in captivity until she died of a parasitic infection in August 1973.

Little is known of the breeding habits of Killer Whales. From evidence collected during varying stages of fetus development taken from females commercially by Japanese & Soviet whaling fleets, mating appears to occur throughout the entire year. It is also believed, that the species is perhaps polygamous, mating for life with several females of an individual pod. The male’s penis is completely retractile and on a 22’ bull taken in the Sea of Japan, measures 4.5’ in length and was 2.5’ in circumference. A chance aerial photograph was taken by Dr. Siskan Tukjashima of Japan’s “Kamogawa Marine Mammal Research Center” in June 1967, which revealed a pair in copulation belly to belly near the surface of the water.

Juveniles are extremely playful, cavorting about the adults with apparent youthful enthusiasm. Observers have reported seeing young Killer Whales charging quickly at the heads of the adults resulting in an adult catapulting the calf into the air completely out of the water with their powerful tails. Non-sexually active young males often travel on the outside fringes of the remaining pod members, until they reach stable sexual maturity at approximately 14-years of age. Occasionally while traveling, Killer Whales will leap fully extended above the waterline known as “breaching” and fall onto their sides with a tremendous splash. An individual weighting 8 tons must achieve an exit speed from the water of approximately 30’ per second to clear the surface completely.

The overall purpose of such aerial traits is not completely understood, but some experts believe that it represents an act of an efficient predator with time for play or could be quite simply, another form of communication to other pod members.

While diving, an individual may slap the water’s surface resoundingly with its tail flukes known as “lob-tailing” which is believed to be still another form of pod communication. According to Kenneth C. Balcomb III, Executive Director for the “Center for Whale Research”, most dives are rather short in duration approximately 30 seconds or less. About every fifth dive however, results in a longer duration and while especially feeding on a school of fish, may be expanded from 1-4 minutes in length. During these longer duration dives, a Killer Whale can travel several hundred yards before resurfacing.

Individuals classified as “transients” unlike the better-known “resident” population species, have been recorded to register extremely deep dives lasting between 10-15 minutes in duration, especially when hunting the larger rorqual or baleen whales in the open ocean. Frequently an entire pod will surface & dive simultaneously, even when separated by broad expanses of water. The pod members will correlate abreast like advancing flanks of military troops marching in formation, rising & falling in perfect unison.

The acoustic repertoire of Killer Whales consists of pulsed calls & tonal sounds, called whistles. Although previous studies gave information on whistle parameters, no study has presented a detailed quantitative characterization of whistles from wild Killer Whales. Thus an interpretation of possible functions of whistles in Killer Whale underwater communication has been impossible so far. In this study acoustic parameters of whistles from pods of individually known Killer Whales were measured. Observations in the field indicate that whistles are close-range signals.

The majority of whistles (90%) were tones with several harmonics with the main energy concentrated in the fundamental. The remainders were tones with enhanced second or higher harmonics & tones without harmonics. Whistles had an average bandwidth of 4.5 kHz, an average dominant frequency of 8.3 kHz, and an average duration of 1.8 seconds. The number of frequency modulations per whistle ranged between 0 and 71. The study indicates that whistles in wild Killer Whales serve a different function than whistles of other delphinids. Their structure makes whistles of Killer Whales suitable to function as close-range motivational sounds.

Traveling along coastlines, females & juveniles tend to hold a steady course while the bulls investigate coves, inlets and beaches for potential food sources. This documented trait often sends swimmers & surfers scurrying for apparent safety with fear of a possible attack. Killer Whales have been observed attacking Pacific Walrus (Odobenus rosmarus) which sun themselves on rocks, floating ice blocks or on coastal sand bars. This unique predatory trait has been witnessed during such attacks on other oceanic marine mammals such as penguins & seals found resting on ice floes in both Arctic and Antarctic waters. This particular predatory trait frightens the intended prey so thoroughly, that they panic and dive directly into the water to escape the initial assault, only to be caught immediately into another Killer Whale’s path.

Field research has also shown that Killer Whales off the coasts of Argentina and Brazil have developed this predatory trait to an even higher form of predation. During the months of February through May, the southern hemispheric eastern population of Southern Sea Lions (Otaria flavescens) and Southern Elephant Seals (Mirounga leconina) come to these isolated beaches to give birth and to mate.

The infant pinnipeds begin to investigate the ocean at approximately 3-months of age, unknowing of the dangers that await their discovery of their new oceanic world. Killer Whales in this particular region of the world have become adept by surfing onto the beach front at low tide to prey upon the unsuspecting juvenile pinnipeds. Arriving like clockwork each year at this time, Killer Whales come to this area from their winter grounds in the Antarctic waters to prey upon the abundant food source and teach their young the art of predatory killing. This same form of hunting technique although not as dramatic but just as deadly, takes place on the isolated shores of the North American pacific rim region.

The transient population hunts unsuspecting Steller or Northern Sea Lions (Eumetopias jubatus) and the Northern Elephant Seal (Mirounga angustirostris) within the Baja peninsula region of California & Mexico, along the Pacific coastline of northern Vancouver Island and within Alaska’s vast Prince William Sound expanses. During such attacks, Killer Whales have been seen tossing a pinnipeds into the air repeatedly or simply holding the smaller mammal in their mouth, seeming to play with them. Researchers have theorized that such unique hunting techniques prove a learning facility for young juveniles. The adults have been seen, taking a still-living pinnipeds several miles away from shore and then releasing it for a young Killer Whale learning to use its sonar echolocation to locate an intended prey.

Little scientific information has been obtained regarding the extended distribution or various migratory patterns of Killer Whales. Although worldwide in predatory range, they tend to congregate in the world’s colder oceans, quiet possibly because a diversely more abundance of natural food sources can be located in these regions and the isolation from humans. Large concentrations of Killer Whales occur in several locations throughout the world’s oceans as in the Pacific Northwest rim off the coastlines of Alaska, British Columbia and Washington, where extensive field research has revealed that a large population of over 800 individuals inhabits this particular oceanic zone.

A known-resident population of over 300 individuals inhabits the waters of northern Washington’s Puget Sound and the vast Strait of Juan de Fuca, Georgia Strait, Johnstone Strait, Haro Strait and the Queen Charlotte Strait, which borders the coastlines of mainland British Columbia and Vancouver Island. Between 1979 and 1981, the “Moclips Cetological Society” conducted a “Killer Whale Survey” collecting 24 various sightings of Killer Whales off the coast of Vancouver Island’s “Inside Passage”. This particular body of water which separates Vancouver Island from mainland British Columbia until the early 1970’s, had never been considered abundant with Killer Whales.

A photo-identification field research project conducted by the “Pacific Biological Research Station” located in Nanimo, BC and headed by the facility’s Research Director Dr. Michael A. Bigg, led to the unique project development of a Photo-Identification Catalog displaying each individual Killer Whale and it’s corresponding pod membership.

Other regions of population concentration in large numbers exist near the continent of Antarctica, off the coastlines of Iceland & Greenland and off the southern coast of Australia. Only a few documented sightings of Killer Whales have ever come from the expansive Gulf of Mexico or the warm Caribbean Ocean region.

It is those regions of the world such as the Pacific Ocean rim basin of the North American continent where the colder waters contain a large population of pinnipeds, fish and migrating rorqual whales that Killer Whale sighting occur throughout the year.

A possible subspecies of “dwarf” or “yellow” Killer Whale was described from the ice edge in the Indian Ocean sector of the Antarctic from 60°E to 141°E. The skulls – especially the teeth – of the 6 specimens that were collected differ noticeably from those of most other Killer Whales. During the summer, at least, these small animals are said to range in the same waters as typical Killer Whales but not to mix in the same schools with the latter. The 2 kinds are also said to select different prey – fish as opposed to mammals, respectively. However, further studies are needed to ascertain whether these small whales deserve recognition as a separate species or subspecies.

KILLER WHALE (Wild) INTERACTION CASE STUDIES

In June 1983 while preparing to scuba dive within the Robson Bight Killer Whale sanctuary off the eastern Vancouver Island coastline, noted Marine Wildlife author Dr. Erich Hoyt came across a Killer Whale lying upside-down in just a few feet of water. As he waded towards what he believed to be the carcass of a dead animal, the 27’ bull rolled over and swam into deeper water. It is now suspected that the animal floated in this manner to “play dead” to entice prey such as waterfowl, seals or fish to draw near, but this particular predatory trait may serve to perform yet another life-cycle function within the mysterious world of the Killer Whale.

A team of British scientists in December 1955, were on an Antarctic research expedition and were given a rare opportunity to watch at extremely close range, a small pod of 7 Killer Whales that had become trapped in an icebound inlet. They were entrapped within the large oceanic inlet with 128 Beluga Whales (Delphinapterus leucas) and 4 Fin Whales (Balaenoptera physalus), having been cutoff from the open ocean by a quick change in temperature and ocean current. With an existing supply of available food, the Killer Whales appeared active & healthy. From time to time, individual Killer Whales would breach or raise their heads above the waterline known as “spy-hopping” and watch the scientists intently. One of the animals stuck its head out of the water at the edge of the ice pack and showed very little reaction as a research member poked at its snout with a ski pole. As strange as it may seem to people accustomed to believing Killer Whales as the highest degree of danger that a human being might encounter in the world’s oceans, the basic truth seems to support that the species often display a singular lack of aggressiveness towards humans.

Chief Dive Officer Dr. James R. Stewart of the “Scripps Institute of Oceanography” (now known as the “Sea World Research Institute”), has documented many encounters between humans & Killer Whales over the years. One such encounter occurred off California’s Pismo Beach in May 1955. During a dive session, divers Earl Murray & Conrad Linbough heard a low-pitched sound. Upon surfacing, they saw a female breach less than 50 yards from their surface position.

Off the coast of Mexico’s San Benitos Island in March 1959, a scuba diving team consisting of Dr. Patrick Cunnison, Emil Habecker, Dr. Wheeler North and Dr. Ronald Stewart, saw a mature bull patrolling a small inlet cove that contained some juvenile Northern Elephant Seals. After chasing the whale out of the inlet with their boat, Habecker remained on-board to stand watch while the remaining dive team members entered the water. A little more than 15 minutes into the dive, the submerged members heard rifle shots being fired from the surface. Quickly surfacing, the divers were astonished to find that the Killer Whale was once again at the rear of the inlet, having swum past them while they were submerged. In June 1960, a small pod consisting of 4 individuals approached a pair of divers in La Jolla Cove off the southern California coastline. A large bull came to within 21’ of the rest of the 18 member diving class.

Off the coastline of Cardiff in southern California in April 1967, Dr. North had another extremely close encounter. While on the bottom attempting to free an anchor that had become entangled in some rocks, he heard several low-level sounds. Upon surfacing, he saw a small female breach some 15’ away, look directly at him and then swim away. At the same time, 3 other individuals were within 50 yards of his position. Perhaps one of the closes accounts of a documented attack upon a human in the wild by a Killer Whale, took place off the coast of southern California near Pacific Grove on May 15, 1978.

In an article that appeared in “Skin Diver” magazine, approximately 200 people were onshore when they witnessed a Killer Whale swimming rapidly towards a group of 4 divers. As the divers floated on the surface some 150 yards off southern Vancouver Island’s Lover’s Point, the whale bumped into one of the individuals and sent him spinning. After the frightened divers scrambled on-board their vessel, the Killer Whale reportedly circled their craft for 20 minutes before finally departing.

Several other suspected attacks have been reported over the years and once such incident, appears to have unimpeachable evidence of a Killer Whale attacking a human in the wild. Off northern California’s Point Sur near the Monterey Bay coast, Hans Kretschmer was lying on his surfboard in about 100’ of water on September 9, 1972. He felt something nudge him from behind, looked over his shoulder and gave this account of what happened next.

“I saw a large glossy black object”, the 18-year old told Dr. James W. Hughes, a local Dentist who was part of the rescue team. “At first, I thought it was a large shark, then the animal grabbed me. I hit it on its head with my fist and thought for sure it would come after me again, but it swam off and I was able to swim back to shore.” To surgically close the 3 deep-gashes on Kretschmer’s left thigh required 143 stitches. Sheriff Deputies questioned a short time after the surgery, the teenager about the incident as were a close pair of Kretschmer’s friends.

According to Dr. Hughes, “the boys consistently described an animal that had a large dorsal fin, white markings on the underside of its body and was dark black on top”. Hughes himself an experienced diver and extremely familiar with various oceanic marine wildlife, stated without hesitation that “he was convinced from the young man’s detailed description, that the attacking animal had been a Killer Whale”.

Conclusive evidence of Kretschmer’s attacker came from the attending physician who performed the surgery. Dr. Charles R. Snorf in an extensive statement pronounced, “that the distance between the 3 deep-gashes corresponded to the exact distance found between a Killer Whale’s tooth pattern. Furthermore, the type of wounds inflicted were clean much like deep ax cuts and were just the sort of wounds that would have occurred in a resulting laceration administered by a Killer Whale.

Compared to the typical wounds inflicted by a Shark, both Seal and Sea Lion bites would have left canine-type tooth marks, which would have resulted in a ripping-type of injury display. On the other hand, a Shark would have inflicted a truly devastating wound, which would have resulted in the victim receiving an injury of completely torn-out chunks of large tissue and muscle. If it had been any type of Shark, his hand would have suffered severe abrasions due to a Shark’s extremely rough skin texture”.

That appears to be the only authenticated Killer Whale attack upon a human in the wild, although the noted attack did not result in a fatal injury. The whale probably realizing its mistake, simply left the area giving to the idea that the young man was not it’s intended prey. Steller Sea Lions which are on the prey list, had been observed in the immediate area just prior to the resulting attack.

Preliminary field data has also revealed that this oceanic marine mammal posses all of the human senses with the exception of smell. Essentially a sonic creature who apparently uses its sonar-echolocation capacities to navigate, hunt and communicate with others of its own kind, the case studies discussed thus far do not constitute concrete evidence that a Killer Whale will not attack a human. Current research suggest however, that this ultimate predator of the oceanic food chain may not be the terrible threat to swimmers and scuba divers that it has been reputed to be.

KILLER WHALE (Captive) INTERACTION CASE STUDIES

In captivity, several documented Killer Whale encounters including the ultimate death of a human, have been observed and even recorded on film.

During an afternoon “Whale Show” at Sea World of California in San Diego on April 21, 1979, trainer Annette Echis was riding on the back of a young Killer Whale stage-named “Shamu”. After the 20-year old fell off the whale’s back, “Shamu” turned and began to play “tug-of-war” with Echis’ leg as frantic training team members attempted to pull her leg free from the whale’s mouth. “Shamu” finally released her leg after a final quick tug and she was rushed to an area hospital. The leg wounds suffered by the young woman, required 3 hours of surgery and 177 stitches to close.

Other whales in various Sea Life parks have held their trainers underwater almost drowning them. Most of these rare incidents have happened when a trainer such as Echis, was riding a whale around the pool on its back and hanging onto its dorsal fin. Some of these captive Killer Whales may seem to tolerate these “back riding” performances, but it has been observed that most captive Killer Whales do not like this form of human interaction. Younger individuals new to captivity, frequently allow this type of performance but at an older stage of life, they become independent and rarely allow their handlers to climb onto their backs. Trainers still ride young captive Killer Whales at the Sea World facilities in Ohio, Florida, Texas and California, but the captive animals held in Canadian facilities such as the Vancouver Public Aquarium are no longer ridden. Killer Whales held in the Canadian venues, are viewed in constructed natural habitat settings rather than exploited for a “circus-type” atmosphere.

Several major incidents involving the death of a captive Killer Whale have taken place, especially in the various Sea World facilities. On June 2, 1989 during another typical “Whale Show” at San Diego’s Sea World, trainer Rick Emerson was riding a female Killer Whale stage-named “Kandu” around the main performance pool. Another whale stage-named “Shamu” was scheduled to jump over the trainer and “Kandu” as part of the performance. The show’s choreographer Dick Richardson displayed the wrong hand-signal jester to “Shamu” and instead of jumping over the other whale, instead landed directly on top of both “Kandu” & Emerson. The injured trainer suffered a sever concussion along with a collapsed lung and fractured rib cage and “Kandu” had to be euthanize. “Shamu” received minor lacerations, as several top executives & trainers were fired for the negative public relations event.

A compounded event took place once again at San Diego’s Sea World a few months later, this time involving a Killer Whale fight that led to yet another death of a captive animal. During a show on August 22, 1989, another whale stage-named “Kandu” died from massive bleeding caused by a freak injury. When showing “normal” Killer Whale behavior, she attacked a female stage-named “Corkey” who was attempting to dominate. Sea World veterinarian Dr. Jim McBain stated “that the 2.5 ton “Kandu” attacked the larger 3.5 ton “Corkey” during the facility’s 4:00 pm show”.

McBain continued, “the trainers saw the whales fighting in a holding pen behind the main pool access midway into the hour-long program. They reported seeing “Kandu” charge into “Corkey” with her mouth open. The impact of the whales fractured the smaller Killer Whale’s nasal passages”. The veterinarian said the there was nothing Sea World officials could do to save the smaller whale. As hundreds of spectators watched, “Kandu” spouted large amounts of blood, which stained the water and the sides of the tank. McBain further explained, “the altercation was initiated by the smaller whale. She was asserting her dominance by going after the larger whale with her mouth open. It’s very common behavior for the survival of any species, as the stronger animal has to rule. The death was an unexpected shock, but the altercation was not a rare event at all. It was normal Killer Whale behavior in the wild which was enviably displayed in a captive situation.”

Sea World officials briefly considered canceling the facility’s trademark “Whale Show”. But the suggestion was rejected when trainers argued that it would be better for the remaining whales to continue with a normal day. The scheduled shows continued throughout the day, though without any of the trainers in the presentation pool. The fatal collision between the pair of whales took only about 5 seconds, but “Kandu” lingered with life for about 45 minutes before she died. The expired female had made news in September of 1988, when she gave birth to a baby during a performance.

The birth was videotaped and Sea World’s multiple facilities have been using the tape within their advertising campaign entitled “the birth of Baby Shamu”. Despite the fact that the infant Killer Whale was still nursing, Sea World officials said they were extremely confident that “Kandu’s” death would not have an adverse effect upon the young whale.

McBain finished his statement by saying “the baby whale is feeding on approximately 40 to 45 pounds of solid food a day and is staying with “Corkey” at night. Obviously she realizes that something is completely different as the infant Killer Whale appears to be awaiting her mother’s return, but we think she’ll do all right at the final outcome. “Corkey” suffered superficial cuts & bruises, but was otherwise uninjured in the incident.”

At Oak Bay, British Columbia on February 22, 1991 at Sealand of the Pacific, the ultimate Killer Whale vs Human incident took place. During the small facility’s extensive “Whale Show”, a trio of Killer Whales dragged a 22-year old trainer to her death before hundreds of horrified spectators. Senior marine mammal trainer Keltie Lee Byrne fell into the water as she walked along the edge of the performance pool. As other training team members were assisting her out of the water, one of the whales grabbed her foot and pulled her back into the performance pool. The remaining pair of Killer Whales then proceeded to grab other portions of Byrne’s body and together, the trio of Killer Whales dragged the helpless trainer to the bottom of the pool before releasing her body.

Current scientific studies are underway which may lead to answers for such behavioral traits with captive Killer Whales. Most members of the scientific community believe that the enclosure of oceanic marine mammals who use a high degree of intelligence combined with their use of known sonar-echolocation, is severely restricted & depleted by the standard poured-cement walls of their enclosure tanks. A mundane existence from a captive Killer Whale’s normal day to day routine in the wild, may lead to a depletion of their normal mental state of mind as well. Scientists liken such mental stability theories to that of the known experiences of individuals held captive in “prisoner of war” camps during World War II and the Viet Nam conflict.

During a personal visit to Sea World of Florida in Orlando in May of 1984, the facility’s marine mammal research director Dr. Edward M. Asper showed me an aging bull that was kept in an observation tank away from the general public and was used strictly for observation and research. Dr. Asper explained that the large 26’ Killer Whale had killed several Bottlenose Dolphins (Tursiops truncates) and had even taken a grab at a woman who had gotten too close to his pool.

Dr. Asper jokingly informed me that there was a standing offer of $500.00 to anyone who would swim completely across the old whale’s tank. Needless to say, I declined Sea World’s generous offer. That very strange but true story ended however on August 11, 1985 when the old Killer Whale died.

Vancouver Aquarium commissioned 38-year-old sculptor, Samuel Burich to find and kill an Killer Whale and to fashion a life-sized model for the aquarium’s new British Columbia Hall. He set up a harpoon gun on Saturna Island in British Columbia’s Gulf Islands. Two months later, a pod of 13 Killer Whales approached the shore. Burich harpoons a young whale, injuring but not killing it. “Immediately, several pod members came to the aid of the stunned whale, pushing it to the surface to breathe. Then the whale seemed to come to life and struggled to free itself, jumping & smashing its tail and according to observers, uttering ‘shrill whistles so intense that they could easily be heard above the surface of the water 300 feet away.” Burich set off in a small boat to finish the job. He fired several rifle shells at the whale but the Killer Whale did not die.

The aquarium’s director Dr. Murray A. Newman, soon arrived from Vancouver by float plane and decided to try to save the 15-foot-long 1-ton whale. Using the line attached to the harpoon in its back, Burich and Bauer towed the whale to Vancouver. It took 16 hours through choppy seas and blinding squalls to drag the whale to Vancouver. “Moby Doll” is put into a makeshift pen at Burrard Dry docks and became an international celebrity and a magnet for scientists. The Royal Canadian Navy had recorded Killer Whales in 1956, but no scientific course of study was made of their sounds until “Moby Doll’s” capture.

Drs. William Schevill & William A. Watkins of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute visited “Moby Doll” to study and record her sounds. Scientists and others who observe the whale comment on the whale’s docility & tameness. The whale seemed to be suffering from shock. For a long time, “Moby Doll” would not eat. She was offered everything from salmon to horse hearts, but the whale only circled the pool night & day in a counterclockwise pattern.” After 55 days in captivity, “Moby Doll” began eating up to 200 pounds of fish a day. The whale had developed a skin disease from the low salinity of the harbor water and continued to appear exhausted. The whale died a month later, after 87 days in captivity. Newspapers around the world chronicle “Moby Doll’s” death. The Times of London gives the whale’s obituary a front page heading, the same size given to the outbreak of World War II. The widespread publicity, some of it the first positive press ever about Killer Whales, marked the beginning of an important change in the public attitude toward the species. The necropsy revealed “Moby Doll” to be a male, not a female.

“Namu” was only the second Killer Whale captured and displayed in an aquarium exhibit and was the subject of a film that changed some people’s attitudes toward Killer Whales. In June 1965, William Lechkobit found a 22-foot male Killer Whale in his floating salmon net that had drifted close to shore near Namu, BC. The Killer Whale was sold for $8,000 to Edward “Ted” Griffin, a Seattle public aquarium owner but it ultimately cost Griffin $60,000 to transport the bull some 450 miles in a floating pen to Seattle.

“Namu” was an extremely popular attraction at the Seattle aquarium and Griffin soon captured a female to be a companion for “Namu”. The female whom Griffin named “Shamu”, did not get along with “Namu” however and “Shamu” was eventually leased to Sea World in San Diego. “Namu” survived one year in captivity and died in his pen on July 9, 1966. Although the young male Killer Whale “Moby Doll” was the first live Killer Whale exhibited in captivity, he survived less than 90 days in captivity. “Namu” was the first Killer Whale to survive in captivity long enough for a significant public exhibit. The United Artists film ”Namu, the Killer Whale” was released in 1966 and starred “Namu”, Robert Lansing and Lee Meriwether in a fictional story set in the San Juan Islands. The name “Namu” was also later used as a show-name for different Killer Whales in Sea World Adventure Parks shows.

Regardless of the documented events which have taken place in various captive situations, the Killer Whale is still considered the most formidable predator in all the world’s oceans. Combining strength with an extremely high degree of intelligence along with a swimming rate, which has been recorded of obtaining a top speed of 35 mph, this powerful oceanic marine mammal in the wild has no equal.

KILLER WHALE (Historic) INTERACTION CASE STUDIES

It might be argued that sharks as well, often approach humans without attacking but the comparison must end at that point. Each year, many reported and documented attacks by sharks occur, yet my research to this point has been able to uncover a single authenticated report of a Killer Whale fatally killing a human in the wild, which is not the case of the Elasmobranches, the family of sharks, rays and skates.

This scientific statement is especially significant when considering the fact that Killer Whales feed mainly on warm-bloodied animals and have been documented killing such animals in wholesale quantities. There have been many reports of Killer Whales smashing the sides of boats with their heads or tails. These are attacks in a very broad sense, but virtually all such incidents have occurred after an animal had been shot, harpooned or otherwise molested. Marine biological researchers have discovered that in most cases even with the strongest provocation, such retaliatory acts are indeed, extremely rare. One such incident however, occurred on March 11, 1952. It was one of some of the most widely reported attacks upon a vessel that perhaps, has ever been erroneously charged to a Killer Whale.

After a very large oceanic marine animal attacked a light sailing yacht off the coast of Los Angles puncturing the craft’s hull with its teeth, the pair of terrified occupants blamed the reported attack on a Killer Whale. The story was given credence by newspapers and even by a noted marine scientist. Photographs of the boat’s hull and careful examination of the crescent-shaped row of tooth marks on the vessel’s side however, strongly suggested that a very large shark had done the attack. Oceanic marine biologists on the inspection team believed after further study of the tooth patterns, that this attack had come from a Great White Shark (Carcharodon carcharias).

In another much published case that reportedly occurred on February 17, 1973 off the coastline of South Africa, a Killer Whale was reported to have sunk a boat and to have eaten 4 of the 6 occupants on-board. Upon further investigation however, marine biologist Dr. Joseph L. Smith of the I.W.C. (International Whaling Commission) stated that “the attacking animal was much too large to have been a Killer Whale and was probably either a Sperm Whale (Physeter macrocephalus) or a Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus) that perhaps believed that its calf was in some form of danger or quite simply, did not notice the vessel in its way.

It was a few days later that the missing individuals had died from drowning after discovering their bodies washed-up on an isolated South African beach near Cape Town. Upon medical examination of the bodies, there was found to be no form of evidence to support any claim that a Killer Whale had killed any of them.

One of the most widely quoted attacks by Killer Whales in the wild, took place during the 1911 “Terra Nova” expedition headed by Commander Robert F. Scott on the Antarctica continent. Scott’s research team had just tied-up their sled dogs on an adjacent ice floe on the outside of their campsite. The animals became very unsettled, as a pod of 11 Killer Whales appeared in the immediate area and occasionally stuck their heads up through the ice to take a look at the confined dogs. After the expedition’s chief photographer Ivan Ponting went out to the ice floe to film the whales, the Killer Whales quickly dove and disappeared. A few minutes passed, when the whales reappeared and began to smash the 5’ thick ice directly between the frightened dogs & Ponting. He ran from the ice floe as the whales repeatedly rammed their heads up through the frozen surface. After several minutes, the whales once again dove and disappeared from the scene. Whether or not the Killer Whales were trying to catch Ponting, the dogs or both will never be known. Even if the whales viewed the photographer as a prospective dinner, it is quite possible to ascertain that the Killer Whales simply mistook him and the dogs for either a seal or sea lion.

Popular literature is replete with the tales of Killer Whales attacking the largest members of the Cetacean family, the great baleen whales. Generally such attacks are made by an entire pod, usually numbering between 10 to 21 individuals working together much as a pack of wolves hunting a Caribou or Deer.

One such attack was filmed on October 14, 1979 by a scientific research team under the direction of the National Geographic Society who came upon an attack by 30 Killer Whales on a young 51’ Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus). On May 22, 1981, a group of marine biologists from the Hubbs/Sea World Research Institute photographed another such attack by 17 Killer Whales on an adult female 49’ Grey Whale (Eshrichtius robustus) off the Baja coast near San Diego, CA. Another dramatic opportunity to film the violence of a Killer Whale attack in the wild, came on May 12, 1992 as researchers came upon the attack of a female Grey Whale and her young calf off the coast of California’s Monterey Bay. The pod of 8 Killer Whales including 2 large bulls, completely devoured the infant whale and mortality wounded its mother, as she fled the bloody scene. Several adult male Grey Whales were in the immediate area, but did nothing to prevent the onslaught and simply stayed out of the killing zone.

The powerful jaws of a Killer Whale make little headway against the extremely thick layers of blubber found in a large adult rorqual whale. The tail flukes of these large whales can inflict tremendous damage or even mortally wound the smaller Killer Whale. Therefore, the Killer Whale usually prey upon the young, injured or aging baleen whale. Often after they have herded a pod of these larger rorqual animals into a panic-stricken group or after a baleen whale has been harpooned by commercial whalers, a few Killer Whales may hold onto the flukes while the remaining pod members force their heads in between the defenseless jaws of the intended prey. During a 1988 field study of Grey Whales, the Executive Curator of Marine Mammals for Sealand of the Pacific Dr. LeRoy S. Andrews found that 7 out of 35 whales within the study area off the coastline of southwestern Vancouver Island, had lost all or a significant portion of their tongues to attacks by Killer Whales.

The whaling industry too, has occasionally reported of the interactions of Killer Whales helping them to defeat & harvest the much larger baleen whales. In at least one region of the world, it has been claimed & written that Killer Whales aided measurably in the profitability of commercial whaling operations. Off the coast of New South Wales at Australia’s Twofold Bay, shore whaling was conducted for more than a century. It was at this location of the world, that Killer Whales are credited with many unique traits suggesting intentional cooperation with humans.

It has been reported in ancient whaling logs, as migrating Humpback Whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) or Southern Right Whales (Eubalaena australis) passed offshore, Killer Whales would swim to the Twofold Bay Whaling Station and attract the whaler’s attention by breaching and lob-tailing just offshore.

The whales would then lead the Twofold Bay Whaling fleet to their intended quarry while forcing the baleen whales into a herded circle by making pinpoint attacks upon the pod leaders. After a Humpback Whale or Southern Right Whale was harpooned, the Killer Whales helped to subdue it by leaping alternatively onto the baleen’s blowhole, thus hampering its breathing while other Killer Whales would swim under the massive body to prevent it from diving. As their reward for assisting in the hunt, the Killer Whales of Twofold Bay were allowed to eat the tongue before the whalers harvested the baleen whale. The whaling men of Twofold Bay recognized many of the Killer Whales by sight and even gave them names such as “Old Tom”, “Cooper” and “Hooker”, the latter so named because of its broken dorsal fin. The whaling men had the friendliest of feelings towards the Killer Whales of Twofold Bay and so tight was their bond with these oceanic marine predators, that it was a criminal offense within the region to ever harm one with a penalty for doing so, death by hanging. On those occasions when a chase boat capsized at sea, it was said that the Killer Whales often hovered near the swimming men until they could be rescued by another vessel.

The shore whaling activities ended at Twofold Bay in 1928. By then, most of the approximate 109 Killer Whales that had frequented this region for more than 70 years had either died or disappeared. One whale however, stayed around the Twofold Bay region until August of 1930, when he died and was found floating in the bay. The skeleton of “Old Tom” was preserved and is currently on display at the Eden Killer Whale Museum in Eden, NSW Australia.

Photograph of “Old Tom” with the Eden whalers

Skeleton of “Old Tom” at the Eden Killer Whale Museum

NORTHWEST PACIFIC FIELD RESEARCH DEVELOPMENT

To continue my inquiry into the ongoing research of the Killer Whale, the most probable region in the world would be the Pacific Northwest basin area of the North American continent. Thought by most marine biological researchers to contain one of the largest known populations of Killer Whales anywhere in the world’s oceans, it seems to be the most logical place to acquire current research and informational studies regarding these awesome oceanic marine mammals.

Killer Whales cruises the cold, plankton-rich waters of the Pacific Northwest during the entire year, from the southern coastline of Alaska’s Prince William Sound to as far south as the inlet waters of Seattle’s Puget Sound. Field research conducted has of yet, determined the exact population density within this vast region, though information & photographs secured by various ongoing field research stations and wildlife organizations currently estimate the number to be in access of well over 800 animals. Within this area, the social instincts of the species has been until recently, exploited for the purpose of capture and sale to public aquariums worldwide.

By firing a 16” harpoon into the back of a large adult cow presumably the pod’s matriarchal leader, a brightly colored float then trails from the harpoon and allows researchers to follow a pod for days. Ian McAskie and Dr. Michael A. Bigg were on one of these photo-identification research trips following a pod from their research vessel.

Within one of the many small natural inlets off the eastern coastline of British Columbia’s Vancouver Island, their boat was drifting quietly tailing a pod of 9 whales. McAskie started the boat’s engines to get closer to the animals when suddenly, 5 of the whales “spy-hopped” at the water’s surface some 140’ from their craft. The floatation device that was trailing the large cow, was found drifting just offshore 4 days later, some 16 miles from the original sighting.

Dr. David E. Caldwell of the University of Oregon’s Marine Mammal Biological staff summarized the care-giving behavior of Killer Whales during a field expedition conducted on April 22, 1980. A field research team in which he directed, came upon an injured female that was seen swimming beside her dead calf. The research team observed her circling the lifeless body for more than an hour until she too, eventually died. Even though local fishermen had shot both the female and her calf with rifle fire presumably, she never attacked the research vessel or displayed any signs of hostility toward the research team. She only continued throughout, to support her dead calf’s body during the short time she as well, remained alive.

Another strange episode regarding this type of Killer Whale behavior was recorded as a research team headed by Marineland of the Pacific’s Marine Mammal Research Director Dr. William L. Casey, captured a large female near Bellingham, WA on May 17, 1976. The rope, which had been thrown around her tail, became entangle in the ship’s propeller and Dr. Casey recounted the scene of the tragic accident that unfolded. “As the female Killer Whale struggled in the water, she emitted a series of low-level penetrating vocalizations. Within 20 minutes. the tail dorsal of her assumed companion male appeared. The bull closed in on the vessel’s hull at a high rate of speed, veering off only when he came extremely close to the boat’s hull. The animal then circled the rapped female slowly.

Within minutes, both whales then charged towards the boat, coming to within 5’ of the vessel. Charging once again, the pair struck the boat’s hull, sending the research members on-board sprawling onto the deck. The crew members grabbed their rifles and were forced to fire upon the animals and kill each in order to save the vessel and avoid any further damage to both the boat and quite possibly, to the individuals on-board”. This unfortunate capture incident was eventually translated into Dino de Laurentiis’ featured 1977 movie “Orca, the Killer Whale” starring Bo Derek, Charlotte Rampling, Keenan Winn, Richard Harris, Will Sampson and Robert Carradine and led to a continuing public outcry for the overall safety & scientific review of the various humane methods that were at that time, acceptable for the capturing & transporting techniques of Killer Whales and other small cetaceans.

The longest recorded time lapse for a Killer Whale to ever live in captivity to date is 18 years. The maximum life span of a Killer Whale in the wild as ascertained by current field research is on the average of 40-50 years for males and 70-90 years for females. Though these animals have tremendous recreational appeal, they are found to have no true commercial value, especially within the United States or Canada. In Asian waters however, Killer Whales are hunted for their fine clear oil, fresh meat for human consumption and for scrap meat used in fertilizer & fish bait.

The natural ability of some small cetaceans to communicate underwater was proven during the mid-1950’s by the Royal Canadian Navy’s Marine Research Center. Recorded vocalization and acoustical subsurface sounds among the Queen Charlotte Islands off the northern coast of mainland British Columbia and Vancouver Island during the summer of 1956 were analyzed. These studies found that the slowdown playback of the vocalization responses recorded by the Center’s Director of Research Dr. Wilson E. Schedvill of captured and cropped Killer Whales, were found to be individual clicks. These individual clicks when fast-repeated, resembled a human scream. The strident-scream & clicks are apparently used for communication and individual responses to other members of the species.

The separate clicks apparently determined echolocation readings or in simple terms, provides a “living” radar system that is used for an individual whale’s navigation. Some researchers believe that the failure of this echolocation system, may be a direct cause for Killer Whales as well as several other species of cetaceans, to run aground while navigating in shallow water. Among the hundreds of such recorded strandings, is the August 1965 mass death of 65 Killer Whales on an isolated New Zealand beach.

Sympathetic onlookers at the scene, tried to save a few of the whales by heading them back out to sea, only to have them simply turn back and die with their companions. Ongoing field research studies continue to ascertain a discovery answer for this puzzling phenomena and better understanding to perhaps assist in solving this perplexing problem.

POPULATION & PHOTO-IDENTIFICATION FIELD RESEARCH STUDIES

The scientific field research study of existing Killer Whale populations within the Northwest Pacific basin began in March 1972 and extending through the summer of September 1975. During this period of time, Canadian Oceanic Marine Biological researchers Graeme Ellis, Dr. John K.B. Ford, Ian McAskie and Photo-Identification Project Director Dr. Michael A. Bigg, correlated their expertise with Killer Whales and other small cetaceans to develop a standard photographic census technique program. Using various 35-mm cameras with telephoto lens and fast-film which provided basic information on population size and distribution, they compared individual Killer Whale profile “mug shots” and found they could identify an individual animal by its characteristic dorsal fin size & shape, the “saddle patch” region’s size & shape as well as both area’s distinguishing marks & scars. The photos were then cataloged with a corresponding letter by which was indicated a specific pod unit with a corresponding number which then referred to an individual whale within a certain pod.

Dr. Graeme Ellis, Dr. John K.B. Ford and Dr. Michael A. Bigg

During this 5-year Canadian study, various pods were photo-documented on 340 different encounters, ranging from southern Puget Sound to the extreme northern end of Vancouver Island. An overall account of 11,641 photographs, showed at least 20 different pods with individual numbers of approximately 210 individual whales. To enhance the Canadian information, further documentation of encounters within the northwest United States region of Puget Sound and the numerous San Juan islands, the Marine Mammal Division of the National Marine Fisheries Services contracted Kenneth Balcomb III, Research Director for the Moclips Cetological Society to conduct a similar field study within American waters.

Designating the unique project as the “Killer Whale Survey”, the Moclips Cetological Society began working directly with the Canadian researchers under the auspices of the University of Washington’s Marine Mammal Biology Center with experimental radio-tagging procedures of Killer Whales within the ever-expanding study area.

Using available media advertisements and the selling of public items such as posters & t-shirts, the “Killer Whale Survey” established a sighting network of interested citizens of both countries who would call a “Killer Whale 1-800” hotline whenever Killer Whales were spotted within the designated study region. Phone calls were accepted around the clock, with all sightings then relayed to field personnel who were prepared to respond in several small chase boats. When field staff encountered the sight Killer Whales, high-resolution 35-mm photographs of as many individual whales as possible were taken.

Using motorized Nikon cameras with 105-mm, 200-mm and 300-mm lenses, only black & white photos were taken instead of color, to prevent any possible shadows and to provide a clearer detailed image of the designated identification markings. Depending upon the existing daylight & time of day, Plus-X and Tri-X film was used. Some color work was accomplished however for various media informational release, using Kodachrome 25 & 64 film combined with high-speed Extachrome film.

The overall base objective of the survey, was to gather as much photographic information as possible, which would give a incise correlation of the current distribution, natural biological habitats, distinct social behavior and hopefully, the overall population dynamics of Killer Whales within the specified region of study.

During a selected 7-month study period in 1976 from April through October, 74 various encounters were made with 6 different pods totaling approximately 83 individual animals. Field personnel followed these various pods for 236 hours, as these encounters tracked over 750 nautical miles, averaging an approximate 3.2 knots per encounter speed. Nearly 700 sightings were received through phone calls from the general public and field personnel logged 13,641 nautical miles and over 1,396 hours in survey chase vessels. During this period of time, approximately 17,000 35-mm black & white photographs of individual whales within the study region were taken, studied and cataloged.

While there is still much to learn about the base-ecology of the Northwest Pacific population, a comprehensive understanding has been reached about the number of Killer Whales present. Through the combined efforts of the Canadian & United States research teams, a sizable block of information has been assembled and studied. The net results of 3 preliminary studies, has served as a baseline to direct future selected resource management decisions and to hopefully assist in conducting future correlating field research projects.

The basic Killer Whale social unit is known as a pod, which appears to be an extended genealogical family format, usually numbering from 5 to 20 individual members. About 20% of an average pod is composed of adult males. As a standard rule, for each bull there is 1 calf or juvenile member within a pod. The remaining 80% are either females or sub-adult females/males. A typically standard pod composition is an extremely cohesive unit with members usually traveling together within a few miles of each other, but most of the time even closer.

The known resident population of this particular region consists of 4 main pods totaling approximately 72 animals and are found throughout the Georgia Strait, Queen Charlotte Strait, Strait of Juan de Fuca, Johnstone Strait and the southern waters of Puget Sound. On extremely rare occasions, a combined mixture of resident pods intermingle for short intervals to form a “super pod” which can number from 47 to 138 whales.

Another sub-species of Killer Whale is found within the region and are known as transients. Their numbers have been systematically identified within 9 pods totaling approximately 58 individuals. These pods however, appear at irregular times of the year and do not associate with the region’s resident population.

NORTHWEST PACIFIC FIELD RESEARCH STUDIES

Early in the “Killer Whale Project”, researchers were puzzled by the fact that a few individual pod encounters had different behavioral patterns from the majority of the region’s population along with subtle differences in their appearance as well. These pods traveled in much smaller groups and were not as abundant during any time of the year. It was felt that these animals were perhaps, outcasts from larger groupings and were in transit to other possible locations. Researchers termed these smaller groups as “transients” and further field research has discovered that these particular animals are probably a separate race of Killer Whale, although the evolutionary relationship between residents and transients still remains a mystery. The most obvious distinguishing feature between residents & transients is their overall size and feeding behaviors. Resident pods contain from 5 to 20 members, whereas transient pods contain from 2 to 7 individuals. There are approximately 350 resident whales within the Northwest Pacific study region compared to approximately 80 transient whales.

Although pods of resident whales are seen during all months of the year, they are most common during May through October. Transient whales on the other hand, appear sporadically in about the same numbers throughout the year, especially during the later portions of August through October when juvenile Steller Sea Lions and Northern Elephant Seal pups begin to take to water combined with the annual migration patterns of the Grey Whales.

While this may lead to an apparent contradiction in terms, it is believed that existing terminology best describes the pair of races. Transients roam throughout a large range of up to 1,900 nautical miles along the coastlines and are rarely seen. Residents on the other hand, range only about 500 nautical miles along the coastlines and are frequently seen throughout an entire year, especially in April through October. It is not known to what extent of nautical mile range either race of Killer Whale travels off shore into the Pacific Ocean basin during the winter months from the Sea of Japan to the northern Arctic Ocean region.

The known resident race has an established northern & southern community. The northern community’s range extends from mid-Vancouver Island north to the southeastern coast of Alaska. The range of the southern community extends from the southern most border of the northern community south into Puget Sound, around southern Vancouver Island and into the coastal Pacific Ocean basin of Grays Harbor, WA.

Each community’s pod population seems to travel throughout their known habitat range, but rarely enter into the known habitat range of the other. Transient pods seem to comprise a single community, which travels throughout both of the local community’s known southern coastal range of British Columbia and Washington to the Queen Charlotte Islands and as far north as the western coastal range of Alaska. Ongoing field research has never documented seeing resident & transient pods traveling together. Each distinct race of Killer Whale at various times of the year especially in August through October when vast schools of salmon migrate to their inland rivers, sometimes pass to within 100 yards of each other, although researchers have yet to record any form of aggression or negative reaction between the pair of Killer Whale sub-species.

The known travel and dive patterns of the races also differ. Residents tend to travel along rather predictable coastal routes, generally from headland to headland. They rarely change directions abruptly unless in pursuit of prey or existing boat traffic. Transients enter small bays not normally visited by residents and often change travel directions suddenly, even when not foraging for a food source. Residents are recorded to have fairly routine dive patterns of 3 to 4 short dives of approximately 15 seconds in length. Transients at most times, have similar dive patters although some dives last from 5 to 10 minutes in length due to their specialized diet of marine mammal prey. These differences, along with the smaller overall pod size, make transients much more difficult to locate & follow.

Another interesting difference is the variation in known dietary habits between resident & transient whales. Residents come inshore during the summer months to feed mainly on large schools of various fish, which aggregate within the narrow coastal “Inside Passage” of mainland British Columbia and Vancouver Island. There have been a few recorded instances of Resident’s preying upon an oceanic marine mammal, but this form of substance diet is probably not a common food source. Transient Killer Whales on the other hand, seem to seek various oceanic marine mammals including migrating baleen whales as their main source of diet. When their normal marine mammal prey is not available, fish may also be part of their dietary format.