“Monachus monachus”

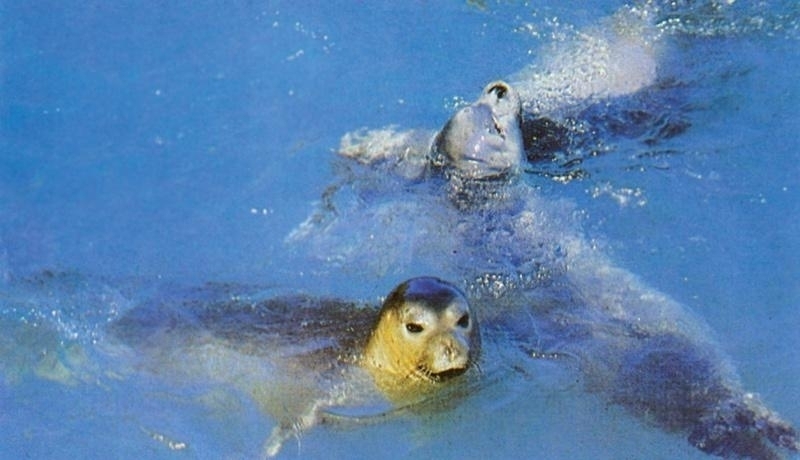

The Mediterranean Monk Seal is one of the world’s most endangered marine mammals with fewer than 600 individuals currently surviving. Their common name is from the excess folds of skin around the seal’s neck causing them to look like they’re wearing a monk’s robe and for the fact that this is a solitary species usually found alone or in very small groups. The species is described as ”critically endangered” by the World Conservation Union (IUCN) and is listed on Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). In ancient Greece, Mediterranean Monk Seals were placed under the protection of Poseidon & Apollo because they showed a great love for sea & sun. One of the first coins minted around 500 BC, depicted the head of a Mediterranean Monk Seal and the creatures were immortalized in the writings of Homer, Plutarch and Aristotle. To fishermen & seafarers, catching sight of the animals frolicking in the waves or loafing on the beaches was considered to be an omen of good fortune. When born, pups measure 88-103 centimeters in length and weigh 15-20 kilograms. Unlike the Hawaiian Monk Seal, Mediterranean Monk Seal pups are born with a white belly patch on the otherwise black to dark chocolate, woolly coat. Extirpated from much of its original habitat by human persecution & disturbance, females now tend to give birth only in caves in remote areas, often along desolate, cliff-bound coasts. Males & females are thought to reach sexual maturity between 5 and 6 years, although some females may mature as early as 4 years. Although pups may be born during any part of the year over most of the species’ current distribution range, pupping takes place almost exclusively in autumn. Mediterranean Monk Seal pups can swim & dive with ease by the time they are about 2 weeks old and are weaned at about 16-17 weeks. Mediterranean Monk Seals are mainly thought to feed in coastal waters for fish & cephalopods, such as octopus and squid. Individuals are believed to live up to 20-30 years in the wild. The Mediterranean Monk Seal averages 2.4 meters in length (nose to tail) and is believed to weigh 250-300 kilograms. Females are only slightly smaller than males. Adult males are black with a white belly patch; adult females are generally brown or grey with a lighter belly coloration. Other irregular light patches are not unusual, mainly on the throats of males and on the backs of females; this is often due to scarring sustained in social and mating interactions.

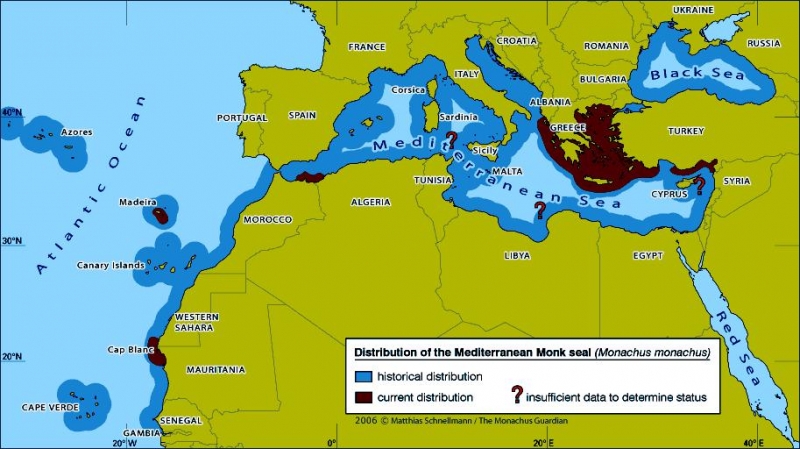

Humans hunted Mediterranean Monk Seals for the basic necessities of their own survival – fur, oil, meat, medicines – but in early antiquity did not kill them in large enough numbers to endanger their existence as a species. Because of their trusting nature, they were easy prey for hunters & fishermen using clubs, spears and nets. The pelts were used to make tents and were said to give protection against Nature’s more hostile elements especially lightning. The skins were also made into shoes & clothing and the fat used for oil lamps & tallow candles. Because the animal was known to sleep so soundly, the right flipper of a seal placed under a pillow was thought to cure insomnia. The fat was also used to treat wounds & contusions in both humans and domestic animals. Evidence suggests that the species was severely depleted during the Roman era. Following the fall of the Roman Empire, a reduction in demand may have allowed the Mediterranean Monk Seal to stage a temporary recovery, but not to earlier population levels. Commercial exploitation peaked again in certain areas during the Middle Ages, effectively wiping out the largest surviving colonies. Increasingly, survivors no longer congregated on open beaches & headlong rocks, but sought refuge along inaccessible cliff-bound coasts and in caves often with underwater entrances. The massive disruption of 2 world wars, the industrial revolution, a boom in tourism and the onset of industrial fishing all contributed to the Mediterranean Monk Seal’s decline and subsequent disappearance from much of its former range. Mediterranean Monk Seals mostly seek refuge in inaccessible caves, often along remote, cliff-bound coasts. Such caves may have underwater entrances, not visible from the water line. Known to inhabit open sandy beaches & shoreline rocks in ancient times, the occupation of such marginal habitat is believed to be a relatively recent adaptation in response to human pressures including hunting, pest eradication by fishermen, coastal urbanization and tour activities. At one time, the Mediterranean Monk Seal occupied a wide geographical range. Colonies were found throughout the Mediterranean, the Marmara & Black Seas. The species also frequented the Atlantic coast of Africa, as far south as Mauritania, Senegal and the Gambia as well as the Atlantic islands of Cape Verde, the Canary Islands, Madeira and the Azores. More recently however, the species has disappeared from most of its former range with the most severe contraction & fragmentation occurring during the 20th century. Nations and island groups where the Mediterranean Monk Seal has been extirpated during the past century include France and Corsica, Spain and the Balearic Islands, Italy and Sicily, Egypt, Israel and Lebanon. More recently, the species is also thought to have become extinct in the Black Sea.

Despite sporadic sightings possibly of stragglers from other regions, Mediterranean Monk Seals may also be regarded as effectively extinct in Sardinia, the Adriatic coasts and islands of Croatia and the Sea of Marmara. Reports also suggest that the Mediterranean Monk Seal may have been eradicated from Tunisia. Similarly, only a handful of individuals reportedly survive along the Mediterranean coast of Morocco. As a result of this range contraction, the Mediterranean Monk Seal has been virtually reduced to 2 populations, one in the northeastern Mediterranean and the other in the northeast Atlantic, off the coast of northwest Africa. Interchange between the two populations is thought improbable given the great distances separating them. The Mediterranean Monk Seal is particularly sensitive to human disturbance, with coastal development & tourism pressures driving the species to inhabit increasingly marginal and unsuitable habitat. In some pupping caves, pups are vulnerable to storm surges and may be washed away and drowned. Unforeseen or stochastic events, such as disease epidemics, toxic algae or oil spills may also threaten the survival of the Mediterranean Monk Seal. In the summer of 1997, two-thirds of the largest surviving population of Mediterranean Monk Seals were wiped out within the space of 2 months at Cabo Blanco (the Côte des Phoques) in the Western Sahara. While opinions on the precise causes of this epidemic remain sharply divided, the mass die-off emphasized the precarious status of a species already regarded as critically endangered throughout its range. The main threats arrayed against the Mediterranean Monk Seal include: habitat deterioration and loss by coastal development, including disturbance by tourism & pleasure boating; deliberate killing by fishermen & fish farm operators who consider the animal a pest that damages their nets and ‘steals’ their fish particularly in depleted coastal fishing grounds; accidental entanglement in fishing gear leading to death by drowning; decreased food availability due to over-fishing pressures; so-called stochastic events such as disease outbreaks.