“Carukua barnesi”

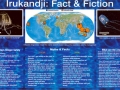

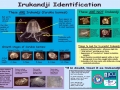

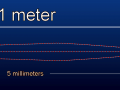

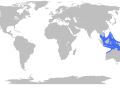

Right from the start, the proper scientific name for these animals is “Sea Jelly” not “Jellyfish”. They are invertebrates and not a fish nor do they have a backbone. The Irukandji Sea Jelly inhabits northern Australian waters and are named after the Irukandji people whose country stretches along the Australian coastal strip north of Cairns, Queensland. This is a very deadly sea jelly, which is only 2.5 centimeters in diameter making it very hard to spot in the water. This is a species of sea jelly which has become known about in recent years, due to deaths of swimmers in Australia. In 2002, Richard Jordon was stung while swimming off the coast of Hamilton Island. He was a 58 year-old British tourist, unfortunately he died a few days later. This deadly species is related to another very deadly jelly and considered the most dangerous animal on our planet, the Box Sea Jelly. Increasing ocean temperatures & strengthening ocean currents are causing many marine species to migrate pole-wards. Among the species predicted to expand their distribution is the potentially deadly Irukandji Sea Jelly, which are found in tropical regions around the world. With a translucent body that makes them almost invisible in the water, Irukandji Sea Jelly fire venom-filled stingers into their victims which most humans barely feel at first. But up to 2 hours after the sting, people stung by one of these jellies can start feeling multiple symptoms of the debilitating “Irukandji syndrome”.

Those symptoms can include vomiting, generalized sweating and severe pain in the back, limbs or abdomen, a sense of impending doom and a rapid heart beat. While Queensland is a “hot spot” for Irukandji Sea Jelly stings, these jellies have historically been confined to waters north of Gladstone. In March 2007, an adult Irukandji Sea Jelly was recorded for the first time as far south as Hervey Bay, just over 3 hour drive north of Brisbane and there have been numerous reports of people being stung by Irukandji Sea Jelly in this region. Like many species of jellies, the Irukandji have a complex life history. The stage we recognize as a “jelly” is the adult stage. The adults produce larvae that swim to the sea floor and turn into tiny polyps just 1-2 millimeters high, smaller than a match head which can produce more polyps by budding. When conditions are favorable, these polyps change into jellies. However, the relative rates at which temperature & acidity change in the future may influence whether the Irukandji Sea Jelly are capable of moving south. If waters continue to warm but acidification proceeds more slowly than predicted, then the Irukandji could migrate farther south in the short-term. One factor that could be preventing them being a more common sight in the region, is a lack of suitable habitat for the polyps of the Irukandji species. While scientists have never been able to find polyps in their natural environment, adult Irukandji Sea Jellies have been observed spawning near coral reefs on the Great Barrier Reef, suggesting that coral reefs may be their natural habitat.